jazzeum

Four Star General

- Joined

- Apr 23, 2005

- Messages

- 38,444

This was in today's New York Times relating to Rick Atkinson's new book, Day of Battle.

****

WE can climb to the top from here,” said Rick Atkinson, not that it seemed we had much choice. The road ahead, a narrowing dirt path, became impassable. The mad dog that had trailed us halfway up Monte Trocchio fortunately seemed to have lost interest in us and our front tires. We cautiously got out, then clambered over rocks and loose dirt, crunching across bone-dry olive groves planted in steep ranks.

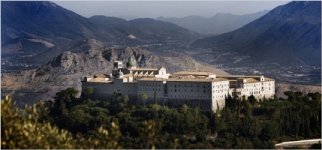

The air smelled of smoke. It was silent and warm. Above the line of olive trees, we trudged the last few yards to the top and from there had a view, the same one beleaguered Allied scouts had in 1944, of the abbey of Monte Cassino and the valley below.

The bookish son of a military officer, Mr. Atkinson had come to meet here at what was one of the deadliest battlefields in World War II, among other reasons because it is, as he agreed, such an “apt metaphor for the war today.” We were speaking especially about the destruction of the abbey 63 years ago.

The second volume of Mr. Atkinson’s trilogy on the liberation of Europe hits bookstores Tuesday (as it happens, in the middle of Ken Burns’s World War II series, “The War,” on PBS).

A longtime correspondent and editor for The Washington Post, the 54-year-old Mr. Atkinson won his second Pulitzer for the trilogy’s opening volume, describing the North African campaign, an often disastrous endeavor that nonetheless helped whip the Allied armies into shape. His second volume, “The Day of Battle,” picks up with the murky story of the campaign in Sicily and Italy, about which there is still angry debate as to whether, unlike Normandy, it was even worth fighting.

Much of the argument centers on this poor, mountainous stretch of towns and farms off the autostrada between Naples and Rome, with its limestone and conifer hills and its Fiat factory, a modern glass anomaly overlooking the cemetery for British soldiers.

Mr. Atkinson surveyed the panorama from Monte Trocchio. He pointed toward Cassino, the hardscrabble city at the base of Monte Cassino, about two miles north. For the Germans, Cassino became the impregnable center of the heavily fortified Gustav Line. For the Allies, fighting their way up the peninsula, it was the obstacle on the road to Rome. After the battle ended it would be left uninhabitable for years, demolished by Allied bombs, beset by malaria. Above it is Monte Cassino, with the abbey on top, like a fortress: “an unblinking eye,” Mr. Atkinson called it. One of the holiest sites in Christendom, founded by St. Benedict in the sixth century, a shrine of Western civilization, it was a center of art and culture dating back nearly to the Roman Empire.

The Germans, Mr. Atkinson said, fired artillery shells from the far side of Monte Cassino. They landed on Trocchio and on Allied troops. “Over there is the Mignano Gap, and a few miles away,” he said, now pointing south, “is San Pietro.”

To reach Monte Cassino, the Allies had to bludgeon through the bottleneck of the gap. The situation summons to mind classic westerns in which narrow mountain passes make sitting ducks of cowboys for ingenious Apaches.

Along the way a pitched struggle unfolded at San Pietro, an 11th-century cobblestone mountain village nestled among wild figs and cactus. That fighting inspired “San Pietro,” a documentary with some restaged sequences directed by John Huston, and a dispatch by the American war correspondent Ernie Pyle, which became a kind of modern-day Song of Roland. As a result, this God-forsaken blip on the map was once the most notorious place in Europe. We scrambled back down to the car, slipping and sliding, to give it a look.

Several miles away, the road forked and deposited us in San Pietro’s piazza. It was an astonishing sight. An antiaircraft gun rusted in the quiet near where the tailor shop used to be. The place was a ghost town, abandoned and forgotten, a Pompeii of World War II, now partly overtaken by vines and lime trees. Winding steps rose steeply to the Church of the Archangel Michael, still bullet-ridden, an echoing shell, its porch shattered, the dead seeming to have just departed.

Past the decomposing carcass of a sheep we finally found the caves, miserable holes clinging to a cliff, where San Pietrans were forced by Germans to live. The corpses of villagers who died from starvation or cold were left below the cliffs because the survivors had no place to bury them.

Just up the hill, Mr. Atkinson said, a 25-year-old captain from Texas named Henry T. Waskow was killed. His company had been heading toward the village when he was cut down by German shell fire. Pyle’s famous dispatch recounted Mr. Waskow’s body being carried by mule and laid down in the shadow of a low stone wall. Mr. Atkinson called it “the finest expository writing to come from World War II.”

It came to be remembered along with the note that Mr. Waskow had sent home with his will. “If I failed as a leader, and I pray God I didn’t, it was not because I did not try,” he wrote to his parents. “I loved you, with all my heart.”

From there to the abbey, we detoured to Sant’Angelo, a dingy rabbit warren of tin shacks and low buildings. Like San Pietro it was demolished during the war, but it has been rebuilt. It overlooks the Rapido River, which close up seems hardly wider than a creek but was fast, deep and fully exposed to German forces above.

In January 1944, Gen. Mark W. Clark, the Allied operational commander here, ordered the attack on that town, which the German 15th Panzer Grenadier Division occupied. The hope was to forge a path to the west around Monte Cassino, through the Liri Valley. It was a debacle. We were standing in the town plaza, overlooking the river, from which the Germans had had a clear line of fire straight down on Allied soldiers, who suffered 2,000 casualties in 48 hours.

“It was such a calamity, and the casualties were so shocking — they were comparable to Omaha Beach — that a number of senior soldiers, Texans, resolved to bring charges against Clark after the war,” Mr. Atkinson said. “But then of course he would also be thought responsible for what happened at the abbey.”

It is tricky to draw analogies with wars of the past, but sometimes comparisons invite themselves. The Germans repeatedly told the Allies they had no soldiers or weapons in the Abbey of Monte Cassino. Julius Schlegel, a Nazi lieutenant colonel, had evacuated manuscripts and art treasures from it. Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, the German commander of the Gustav Line — a former Rhodes scholar at Oxford and an Italophile like most educated Germans, who used to stroll up Monte Cassino with his walking stick surveying the troops and chatting with peasants — had scrupulously followed orders to keep his soldiers far from the building.

Mr. Atkinson pulled the car onto the side of the road that winds up the mountain, where the Gustav Line was located. At 1,500 feet high, the mountain is a steep wall rising straight from the valley. “You have to remember the issue is not whether you can climb but whether you can also carry food, water, ammunition, and do it while you’re being fired at,” he said.

He swung his arm eastward to show where the 34th Infantry Division of the Iowa and Minnesota National Guard, during the dismal cold of January 1944, had fought its way up this mountain and all the way around the back, getting within yards of the abbey before simply running out of steam. We were standing where the Germans had hunkered on the slopes, below the abbey. There were countless nooks in which to dig foxholes and bunkers and make oneself invisible. It was obvious why the enemy hadn’t needed to occupy the abbey on the top of the hill, where in fact they would be more exposed.

But German artillery and gunfire raining endlessly down from the mountain caused Allied troops to imagine that the monastery was the cause of their misery: it was the only thing they could clearly see. One day two American generals flew a Piper Cub over it and believed they spotted Germans in the courtyard. Another general flew by and saw nothing, and a French commander, Gen. Alphonse Pierre Juin, pleaded with the Americans to spare the building, saying an attack was folly.

Those in charge didn’t want to listen. “This monastery has accounted for the lives of upwards of 2,000 American boys,” reported an American Army Air Corps lieutenant colonel to his superiors the day before the attack. “The Germans do not understand anything human when total war is concerned. This monastery MUST be destroyed and everyone in it as there is no one in it but Germans.”

Mr. Atkinson said: “Crummy intelligence leads to crummy tactical decisions. There was a lot of bad intel floating around and a lot of cherry-picking of it.”

It was Clark who ordered the attack. He would spend much of the rest of his life defending this decision, one he had been reluctant to make. He wasn’t sure Germans did occupy the abbey, and instead of stopping them, he predicted, destroying it would only give them another place to hide. “If the Germans are not in the monastery now, they certainly will be in the rubble after the bombing ends,” he warned. But he was overruled.

****

WE can climb to the top from here,” said Rick Atkinson, not that it seemed we had much choice. The road ahead, a narrowing dirt path, became impassable. The mad dog that had trailed us halfway up Monte Trocchio fortunately seemed to have lost interest in us and our front tires. We cautiously got out, then clambered over rocks and loose dirt, crunching across bone-dry olive groves planted in steep ranks.

The air smelled of smoke. It was silent and warm. Above the line of olive trees, we trudged the last few yards to the top and from there had a view, the same one beleaguered Allied scouts had in 1944, of the abbey of Monte Cassino and the valley below.

The bookish son of a military officer, Mr. Atkinson had come to meet here at what was one of the deadliest battlefields in World War II, among other reasons because it is, as he agreed, such an “apt metaphor for the war today.” We were speaking especially about the destruction of the abbey 63 years ago.

The second volume of Mr. Atkinson’s trilogy on the liberation of Europe hits bookstores Tuesday (as it happens, in the middle of Ken Burns’s World War II series, “The War,” on PBS).

A longtime correspondent and editor for The Washington Post, the 54-year-old Mr. Atkinson won his second Pulitzer for the trilogy’s opening volume, describing the North African campaign, an often disastrous endeavor that nonetheless helped whip the Allied armies into shape. His second volume, “The Day of Battle,” picks up with the murky story of the campaign in Sicily and Italy, about which there is still angry debate as to whether, unlike Normandy, it was even worth fighting.

Much of the argument centers on this poor, mountainous stretch of towns and farms off the autostrada between Naples and Rome, with its limestone and conifer hills and its Fiat factory, a modern glass anomaly overlooking the cemetery for British soldiers.

Mr. Atkinson surveyed the panorama from Monte Trocchio. He pointed toward Cassino, the hardscrabble city at the base of Monte Cassino, about two miles north. For the Germans, Cassino became the impregnable center of the heavily fortified Gustav Line. For the Allies, fighting their way up the peninsula, it was the obstacle on the road to Rome. After the battle ended it would be left uninhabitable for years, demolished by Allied bombs, beset by malaria. Above it is Monte Cassino, with the abbey on top, like a fortress: “an unblinking eye,” Mr. Atkinson called it. One of the holiest sites in Christendom, founded by St. Benedict in the sixth century, a shrine of Western civilization, it was a center of art and culture dating back nearly to the Roman Empire.

The Germans, Mr. Atkinson said, fired artillery shells from the far side of Monte Cassino. They landed on Trocchio and on Allied troops. “Over there is the Mignano Gap, and a few miles away,” he said, now pointing south, “is San Pietro.”

To reach Monte Cassino, the Allies had to bludgeon through the bottleneck of the gap. The situation summons to mind classic westerns in which narrow mountain passes make sitting ducks of cowboys for ingenious Apaches.

Along the way a pitched struggle unfolded at San Pietro, an 11th-century cobblestone mountain village nestled among wild figs and cactus. That fighting inspired “San Pietro,” a documentary with some restaged sequences directed by John Huston, and a dispatch by the American war correspondent Ernie Pyle, which became a kind of modern-day Song of Roland. As a result, this God-forsaken blip on the map was once the most notorious place in Europe. We scrambled back down to the car, slipping and sliding, to give it a look.

Several miles away, the road forked and deposited us in San Pietro’s piazza. It was an astonishing sight. An antiaircraft gun rusted in the quiet near where the tailor shop used to be. The place was a ghost town, abandoned and forgotten, a Pompeii of World War II, now partly overtaken by vines and lime trees. Winding steps rose steeply to the Church of the Archangel Michael, still bullet-ridden, an echoing shell, its porch shattered, the dead seeming to have just departed.

Past the decomposing carcass of a sheep we finally found the caves, miserable holes clinging to a cliff, where San Pietrans were forced by Germans to live. The corpses of villagers who died from starvation or cold were left below the cliffs because the survivors had no place to bury them.

Just up the hill, Mr. Atkinson said, a 25-year-old captain from Texas named Henry T. Waskow was killed. His company had been heading toward the village when he was cut down by German shell fire. Pyle’s famous dispatch recounted Mr. Waskow’s body being carried by mule and laid down in the shadow of a low stone wall. Mr. Atkinson called it “the finest expository writing to come from World War II.”

It came to be remembered along with the note that Mr. Waskow had sent home with his will. “If I failed as a leader, and I pray God I didn’t, it was not because I did not try,” he wrote to his parents. “I loved you, with all my heart.”

From there to the abbey, we detoured to Sant’Angelo, a dingy rabbit warren of tin shacks and low buildings. Like San Pietro it was demolished during the war, but it has been rebuilt. It overlooks the Rapido River, which close up seems hardly wider than a creek but was fast, deep and fully exposed to German forces above.

In January 1944, Gen. Mark W. Clark, the Allied operational commander here, ordered the attack on that town, which the German 15th Panzer Grenadier Division occupied. The hope was to forge a path to the west around Monte Cassino, through the Liri Valley. It was a debacle. We were standing in the town plaza, overlooking the river, from which the Germans had had a clear line of fire straight down on Allied soldiers, who suffered 2,000 casualties in 48 hours.

“It was such a calamity, and the casualties were so shocking — they were comparable to Omaha Beach — that a number of senior soldiers, Texans, resolved to bring charges against Clark after the war,” Mr. Atkinson said. “But then of course he would also be thought responsible for what happened at the abbey.”

It is tricky to draw analogies with wars of the past, but sometimes comparisons invite themselves. The Germans repeatedly told the Allies they had no soldiers or weapons in the Abbey of Monte Cassino. Julius Schlegel, a Nazi lieutenant colonel, had evacuated manuscripts and art treasures from it. Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, the German commander of the Gustav Line — a former Rhodes scholar at Oxford and an Italophile like most educated Germans, who used to stroll up Monte Cassino with his walking stick surveying the troops and chatting with peasants — had scrupulously followed orders to keep his soldiers far from the building.

Mr. Atkinson pulled the car onto the side of the road that winds up the mountain, where the Gustav Line was located. At 1,500 feet high, the mountain is a steep wall rising straight from the valley. “You have to remember the issue is not whether you can climb but whether you can also carry food, water, ammunition, and do it while you’re being fired at,” he said.

He swung his arm eastward to show where the 34th Infantry Division of the Iowa and Minnesota National Guard, during the dismal cold of January 1944, had fought its way up this mountain and all the way around the back, getting within yards of the abbey before simply running out of steam. We were standing where the Germans had hunkered on the slopes, below the abbey. There were countless nooks in which to dig foxholes and bunkers and make oneself invisible. It was obvious why the enemy hadn’t needed to occupy the abbey on the top of the hill, where in fact they would be more exposed.

But German artillery and gunfire raining endlessly down from the mountain caused Allied troops to imagine that the monastery was the cause of their misery: it was the only thing they could clearly see. One day two American generals flew a Piper Cub over it and believed they spotted Germans in the courtyard. Another general flew by and saw nothing, and a French commander, Gen. Alphonse Pierre Juin, pleaded with the Americans to spare the building, saying an attack was folly.

Those in charge didn’t want to listen. “This monastery has accounted for the lives of upwards of 2,000 American boys,” reported an American Army Air Corps lieutenant colonel to his superiors the day before the attack. “The Germans do not understand anything human when total war is concerned. This monastery MUST be destroyed and everyone in it as there is no one in it but Germans.”

Mr. Atkinson said: “Crummy intelligence leads to crummy tactical decisions. There was a lot of bad intel floating around and a lot of cherry-picking of it.”

It was Clark who ordered the attack. He would spend much of the rest of his life defending this decision, one he had been reluctant to make. He wasn’t sure Germans did occupy the abbey, and instead of stopping them, he predicted, destroying it would only give them another place to hide. “If the Germans are not in the monastery now, they certainly will be in the rubble after the bombing ends,” he warned. But he was overruled.