TeamMiniatures

Private 2

- Joined

- Oct 21, 2019

- Messages

- 140

Hello to all Collectors!

Here we go again! From May until now, I have taken a break for almost half a year and have not released new products. I am really sorry...

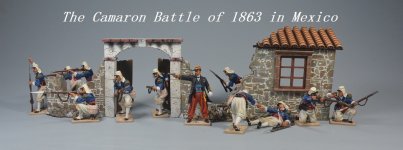

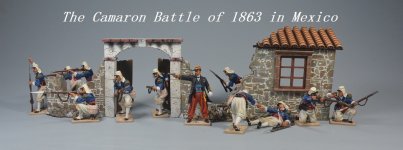

The new product we are announcing is the 1863 Battle of Camarón in Mexico under the command of Capt. Danjou. Despit of the scale of the battle was small, the bravery of the French Troops, who did not surrender even if they died in battle, deserves HIGH PRAISE!

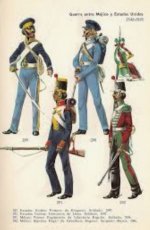

In the future, it will be supplemented by Mexican Soldiers and Irregular Cavalry against the French Troops. They were dressed in strange costumes, and their straw hats with wide brims gave them a special look.

About the preview of the African Chasseurs we released a while back, we're going to launch them after the Battle of Camarón.

As for availability, this time the new product is expected to be completed by the end of December; The African Chasseurs are expected to follow by the end of March 2023. After March next year, new Mongol Soldiers will appear...

Hope the bravery of the French Soldiers at the Battle of Camarón will impress you! Hope you will like these new figures!

Best wishes,

T.M. Jack

French intervention in Mexico dated from 1862, and when their client-ruler Maximilian landed in May 1864 he found that his writ extended no wider than a corridor between Mexico City and Veracruz, maintained with some difficulty by 40,000 troops, many of them French. But by 1864 the Legion’ s greatest battle honour had ever won.

Initially the Legion was employed on patrol, convoy and blockhouse duty in the fever-ridden lowlands of the eastern corridor. A month after their arrival the Legion’s 3rd Company, 1st Battalion, was required to provide escort for a bullion convoy. As all officers in this unit were prostrate with fever, three volunteers came forward. These were the battalion adjutant, Capt.Danjou, a veteran of Algeria, the Crimea and Italy who had left a hand at Magenta; Lt.Vilain, the paymaster; and 2nd Lt. Maudet. Both the latter were experienced officers who had come up through the ranks after enlisting illegally, for they were French citizens; and both had been commissioned for gallantry at Magenta.

Before dawn on 30 April 1863 Danjou set out with his two officers and sixty-two legionnaires. They marched some considerable distance ahead of the convoy. At first light they halted briefly at a Legion outpost, whose commander offered the under-strength escort an extra platoon, but Danjou refused to strip the small garrison of firepower at a time of incessant guerrilla attacks. At about 7.00 a.m. the escort halted for coffee and bread about a mile beyond a derelict settlement named Camerone. Minutes later the sentries sighted horsemen approaching; these were 800 irregular cavalry led by a local officer of revolutionary troops, Col. Milan, who had ridden ahead of his main force of 1,200 infantry after being warned of the convoy’s approach by an informer. The cavalry were well trained and armed with repeating rifles; the Legion at this time carried single-shot Minie weapons.

Danjou formed the habitual hollow square and fell back on Camerone, holding off the cavalry with volley fire; nevertheless, sixteen men and both the supply mules were cut off and captured before the ruins came in sight. They consisted of a two-storey farmhouse, in poor repair but structurally sound, surrounded by a group of outhouses and lean- to sheds grouped around a courtyard, the whole surrounded by a wall. But Mexican snipers were already in possession of the upper storey, and it was under incessant fire that the little group of legionnaires set up a makeshift perimeter in the lower storey, the sheds and around the wall. They fought off several rushes by the dismounted cavalry, but suffered a steady trickle of casualties from the crossfire. By 9.00 a.m. the sun was up, the wounded lay beyond help in the courtyard under the rifles of the snipers, and the Mexicans had drawn closer. A surrender demand was rejected, and Danjou made each man swear not to surrender-some say, on his wooden hand. He was killed by a sniper in the farmhouse at about 11.00 a.m.

Vilain took command, and the 3rd Company held off numerous attacks by the cavalry and the 1,200 infantry who had now arrived on the scene. Thirst and sunstroke added to the torment of the increasingly restricted defenders. Vilain lived until about 2.00 p.m. When he fell Maudet took over, seizing a dead man’s rifle and rallying the defence to the threatened points. Mexican attempts to fire the buildings added choking smoke to the legionnaires’ miseries, and the snipers now overlooked the whole area held by the French. Time and again charges were driven off at point-blank range by disciplined fire from the dwindling band of defenders.

By 5.00 p.m. Maudet had only twelve men left on their feet. He had rejected further surrender demands with choice barrack-room replies, but a massive rush had driven the survivors right out of the farmhouse, restricting them to a few of the out-houses. By 6.00 p.m. he had five men left, and only a handful of ammunition. Knowing that the approaching darkness would bring inevitable defeat, he ordered his five to use their last few rounds. Then they fixed bayonets, pulled aside a barricade, and charge straight across the courtyard at the front ranks of some 1,700 surviving Mexicans.

Milan saw this incredible display of defiance, and managed to save the lives of three of the six- Maine, Berg and Wensel. The others died of their wounds. In all 23 were taken alive from the ruins, of whom 16 survived their short captivity. A single living legionnaire was found under the dead, with eight bullet wounds, by Jeanningros and the relief force which arrived on 1st May, alerted by the convoy which had retreated safely on hearing the gunfire. The wooden hand of Capt. Danjou was also found and taken away, to become a sacred relic. Mexican casualties amounted to some 300 dead and at least as many wounded. The Legion prisoners were well treated and exchanged a month later.

The hopeless defence of Camerone became the Legion’s most highly regarded battle honour, not for its military significance but for the spirit it showed.

Here we go again! From May until now, I have taken a break for almost half a year and have not released new products. I am really sorry...

The new product we are announcing is the 1863 Battle of Camarón in Mexico under the command of Capt. Danjou. Despit of the scale of the battle was small, the bravery of the French Troops, who did not surrender even if they died in battle, deserves HIGH PRAISE!

In the future, it will be supplemented by Mexican Soldiers and Irregular Cavalry against the French Troops. They were dressed in strange costumes, and their straw hats with wide brims gave them a special look.

About the preview of the African Chasseurs we released a while back, we're going to launch them after the Battle of Camarón.

As for availability, this time the new product is expected to be completed by the end of December; The African Chasseurs are expected to follow by the end of March 2023. After March next year, new Mongol Soldiers will appear...

Hope the bravery of the French Soldiers at the Battle of Camarón will impress you! Hope you will like these new figures!

Best wishes,

T.M. Jack

French intervention in Mexico dated from 1862, and when their client-ruler Maximilian landed in May 1864 he found that his writ extended no wider than a corridor between Mexico City and Veracruz, maintained with some difficulty by 40,000 troops, many of them French. But by 1864 the Legion’ s greatest battle honour had ever won.

Initially the Legion was employed on patrol, convoy and blockhouse duty in the fever-ridden lowlands of the eastern corridor. A month after their arrival the Legion’s 3rd Company, 1st Battalion, was required to provide escort for a bullion convoy. As all officers in this unit were prostrate with fever, three volunteers came forward. These were the battalion adjutant, Capt.Danjou, a veteran of Algeria, the Crimea and Italy who had left a hand at Magenta; Lt.Vilain, the paymaster; and 2nd Lt. Maudet. Both the latter were experienced officers who had come up through the ranks after enlisting illegally, for they were French citizens; and both had been commissioned for gallantry at Magenta.

Before dawn on 30 April 1863 Danjou set out with his two officers and sixty-two legionnaires. They marched some considerable distance ahead of the convoy. At first light they halted briefly at a Legion outpost, whose commander offered the under-strength escort an extra platoon, but Danjou refused to strip the small garrison of firepower at a time of incessant guerrilla attacks. At about 7.00 a.m. the escort halted for coffee and bread about a mile beyond a derelict settlement named Camerone. Minutes later the sentries sighted horsemen approaching; these were 800 irregular cavalry led by a local officer of revolutionary troops, Col. Milan, who had ridden ahead of his main force of 1,200 infantry after being warned of the convoy’s approach by an informer. The cavalry were well trained and armed with repeating rifles; the Legion at this time carried single-shot Minie weapons.

Danjou formed the habitual hollow square and fell back on Camerone, holding off the cavalry with volley fire; nevertheless, sixteen men and both the supply mules were cut off and captured before the ruins came in sight. They consisted of a two-storey farmhouse, in poor repair but structurally sound, surrounded by a group of outhouses and lean- to sheds grouped around a courtyard, the whole surrounded by a wall. But Mexican snipers were already in possession of the upper storey, and it was under incessant fire that the little group of legionnaires set up a makeshift perimeter in the lower storey, the sheds and around the wall. They fought off several rushes by the dismounted cavalry, but suffered a steady trickle of casualties from the crossfire. By 9.00 a.m. the sun was up, the wounded lay beyond help in the courtyard under the rifles of the snipers, and the Mexicans had drawn closer. A surrender demand was rejected, and Danjou made each man swear not to surrender-some say, on his wooden hand. He was killed by a sniper in the farmhouse at about 11.00 a.m.

Vilain took command, and the 3rd Company held off numerous attacks by the cavalry and the 1,200 infantry who had now arrived on the scene. Thirst and sunstroke added to the torment of the increasingly restricted defenders. Vilain lived until about 2.00 p.m. When he fell Maudet took over, seizing a dead man’s rifle and rallying the defence to the threatened points. Mexican attempts to fire the buildings added choking smoke to the legionnaires’ miseries, and the snipers now overlooked the whole area held by the French. Time and again charges were driven off at point-blank range by disciplined fire from the dwindling band of defenders.

By 5.00 p.m. Maudet had only twelve men left on their feet. He had rejected further surrender demands with choice barrack-room replies, but a massive rush had driven the survivors right out of the farmhouse, restricting them to a few of the out-houses. By 6.00 p.m. he had five men left, and only a handful of ammunition. Knowing that the approaching darkness would bring inevitable defeat, he ordered his five to use their last few rounds. Then they fixed bayonets, pulled aside a barricade, and charge straight across the courtyard at the front ranks of some 1,700 surviving Mexicans.

Milan saw this incredible display of defiance, and managed to save the lives of three of the six- Maine, Berg and Wensel. The others died of their wounds. In all 23 were taken alive from the ruins, of whom 16 survived their short captivity. A single living legionnaire was found under the dead, with eight bullet wounds, by Jeanningros and the relief force which arrived on 1st May, alerted by the convoy which had retreated safely on hearing the gunfire. The wooden hand of Capt. Danjou was also found and taken away, to become a sacred relic. Mexican casualties amounted to some 300 dead and at least as many wounded. The Legion prisoners were well treated and exchanged a month later.

The hopeless defence of Camerone became the Legion’s most highly regarded battle honour, not for its military significance but for the spirit it showed.