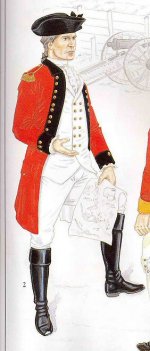

We so need a club figure of this gentleman, preferably in the uniform of a Royal Engineer. The uniform would be the same as Royal Artillery, just Black Facings. He was nearly everywhere except maybe Ticonderoga --- Battle of Monongahela (wounded), Fort William Henry (engineer, internal to the fort itself during the siege, not the encampment), Siege of Louisbourg and the Siege of Quebec (again wounded). He was at Fort William Henry when the French attempt to seize the Fort failed in March 1757, 5 months before Montcalm's successful attempt to take the fort. Plus Bunker Hill later in his career.

His father, George Williamson, commanded the british artillery at the Siege of Quebec and is depicted in the Benjamin West Painting (older gentleman above Wolfe, with just his head showing). The portrait in the link below is when he was a much older gentleman, but at least John would have something to go on. Black Facings - High Snazzy Factor!!!

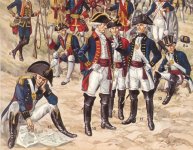

As an aside, still very much want to see an officer conference for the Ticonderoga Release.

Text of link copied below:

Sir Adam Williamson (1733 - 1798)

Following the death of Arthur Jones in 1798, Avebury Manor passed to his chosen successor - Ann (Nanny) Williamson, who‘s husband - Adam Williamson was to become governor of Jamaica. The Williamsons’ owned Avebury Manor between 1789 - 1798

Sir Adam Williamson, army officer and colonial governor, was the son of Lieutenant-General George Williamson (1707?–1781), who commanded the Royal Artillery during operations in North America from 1758 to 1760.

Williamson was educated at Westminster School from October 1744, aged ten. He became a cadet gunner on 1 January 1748, and entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich in 1750.

He graduated as a practitioner engineer on 1 January 1753. The following year he went to North America serving an engineer in Braddock's expedition to Virginia in 1755 where he was wounded during the defeat at Monongahela.

Further conflicts were to follow during his military career; he was at the surrender of Fort William Henry in August 1757 where he was promoted to lieutenant in the 35th foot on 25 September and was given a staff appointment as lieutenant and engineer-extraordinary on 4 January 1758. He served at the capture of Louisburg in July 1758 and the taking of Quebec a year later, where he was wounded again.

He was appointed captain in the 40th foot on 21 April 1760 and distinguished himself during the capture of L'Isle Royale the following August.

Further promotion came in 1770 when he was given the rank of major in the 16th foot and engineer-in-ordinary. Later transferring to the 61st foot; where he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in the army on 12 September 1775.

As lieutenant-colonel of the 18th Royal Irish regiment, he ceased his engineering duties and returned to active service in North America, where he participated in the battle of Bunker Hill (June 1775).

After his return to England in July 1776 he was appointed deputy adjutant-general of the forces in south Britain on 23 December 1778. He achieved promotion to colonel in the army on 15 February 1782 and major-general on 28 April 1790, and became colonel of the 47th foot on 16 July 1790; he transferred to the 72nd highlanders in March 1794.

He had married Ann Jones, at Woolwich on 10th August 1771; she was the daughter of Thomas Jones of East Wickham Kent.

In July 1789, Ann had inherited Avebury Manor from her uncle - Arthur Jones. Sir Adam however, had little time to enjoy his peaceful new country residence, for in late 1790, when war with Spain threatened, he was sent as lieutenant-governor and garrison commander to Jamaica, Britain's most important colony. He was later to replace the governor - Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Howard, 3rd Earl of Effingham following his death in November 1791.

His clemency proved popular with the planters and he won praise for his ‘mildness’ and for maintaining calm after the outbreak of a major slave uprising in nearby St Domingue.

Several of its white colonists sought refuge in Jamaica and requested that Britain take over the French colony. Williamson cultivated these contacts, for St Domingue was a source of enormous wealth. Following the outbreak of war in 1793 he received permission to send troops to those areas that would accept a British protectorate. In September there began a tenuous five-year military occupation. Slave owners welcomed the British forces into much of western and southern St Domingue, and plantation production revived. Ultimately, however, their alliance could make little headway against the burgeoning insurrection among the enslaved and free coloured populations. Troops sent from Europe were vastly outnumbered and died quickly from disease. Yet, in the optimism following the capture of Port-au-Prince on 4 June 1794, Williamson was made a knight of the Bath on 18 November and governor of St Domingue, where he arrived on 26 May 1795.

The governor had to implement an experiment in what later became crown colony government. Reintroducing civil administration into a society torn apart by the French Revolution proved a delicate task. Although Williamson generally had a good word for everyone, his favouring of radical Anglophile colonists over conservative émigrés from France was received badly in Whitehall. The occupation, moreover, became notorious for military losses and escalating costs. Yellow fever, inflation, and the guerrilla warfare of the insurgents doomed the expedition. Williamson expanded the use of black soldiers but was unable to reduce the death rate of British troops. Instructed to foster colonial support for British rule, the humane and generous governor spent lavishly, both his own money and the government's. Since he was fluent in French and fond of late-night drinking and story-telling, he was well liked by wealthy colonists, but, indulgent and overworked, he allowed corruption to flourish around him.

Perceived as a lax administrator and poor judge of men, Williamson was recalled in October 1795; he left the colony on 14 March 1796. His final promotion was as lieutenant-general, on 26 January 1797.

Sir Adam returned to Avebury alone in 1797, for Ann had died of yellow fever whilst they were in Jamaica. Williamson died from the effects of a fall in the dining room/great hall at Avebury on 21 October 1798. It is believed he fractured several ribs in the fall, possibly puncturing a lung. Death would have been slow and painful, his body finally succumbing to respiratory failure.

His obituary in the ‘Gentleman’s Magazine’ of 21 October 1798 reads;

‘At Averbury [sic] House, Wilts, Lieut. Gen. Sir Adam Williamson, K.B. and colonel of the 72nd regiment of foot, and for a short time, governor of Jamaica. His death was occasioned by a violent fall, which fractured two of his ribs, and so terribly bruised him that he languished from Friday till Sunday’.

Source: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited by David P. Geggus. Subsequent edits by Willow

Sir Adam Williamson's funeral hatchments can be found on the south wall of St. James church Avebury. In his will he bequeathed Avebury Manor to Ann’s nephew - Richard Jones.

if no portrait is shown above, see this link

http://aveburymanor.blogspot.com/2012/08/sir-adam-williamson-1733-1798.html

His father, George Williamson, commanded the british artillery at the Siege of Quebec and is depicted in the Benjamin West Painting (older gentleman above Wolfe, with just his head showing). The portrait in the link below is when he was a much older gentleman, but at least John would have something to go on. Black Facings - High Snazzy Factor!!!

As an aside, still very much want to see an officer conference for the Ticonderoga Release.

Text of link copied below:

Sir Adam Williamson (1733 - 1798)

Following the death of Arthur Jones in 1798, Avebury Manor passed to his chosen successor - Ann (Nanny) Williamson, who‘s husband - Adam Williamson was to become governor of Jamaica. The Williamsons’ owned Avebury Manor between 1789 - 1798

Sir Adam Williamson, army officer and colonial governor, was the son of Lieutenant-General George Williamson (1707?–1781), who commanded the Royal Artillery during operations in North America from 1758 to 1760.

Williamson was educated at Westminster School from October 1744, aged ten. He became a cadet gunner on 1 January 1748, and entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich in 1750.

He graduated as a practitioner engineer on 1 January 1753. The following year he went to North America serving an engineer in Braddock's expedition to Virginia in 1755 where he was wounded during the defeat at Monongahela.

Further conflicts were to follow during his military career; he was at the surrender of Fort William Henry in August 1757 where he was promoted to lieutenant in the 35th foot on 25 September and was given a staff appointment as lieutenant and engineer-extraordinary on 4 January 1758. He served at the capture of Louisburg in July 1758 and the taking of Quebec a year later, where he was wounded again.

He was appointed captain in the 40th foot on 21 April 1760 and distinguished himself during the capture of L'Isle Royale the following August.

Further promotion came in 1770 when he was given the rank of major in the 16th foot and engineer-in-ordinary. Later transferring to the 61st foot; where he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in the army on 12 September 1775.

As lieutenant-colonel of the 18th Royal Irish regiment, he ceased his engineering duties and returned to active service in North America, where he participated in the battle of Bunker Hill (June 1775).

After his return to England in July 1776 he was appointed deputy adjutant-general of the forces in south Britain on 23 December 1778. He achieved promotion to colonel in the army on 15 February 1782 and major-general on 28 April 1790, and became colonel of the 47th foot on 16 July 1790; he transferred to the 72nd highlanders in March 1794.

He had married Ann Jones, at Woolwich on 10th August 1771; she was the daughter of Thomas Jones of East Wickham Kent.

In July 1789, Ann had inherited Avebury Manor from her uncle - Arthur Jones. Sir Adam however, had little time to enjoy his peaceful new country residence, for in late 1790, when war with Spain threatened, he was sent as lieutenant-governor and garrison commander to Jamaica, Britain's most important colony. He was later to replace the governor - Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Howard, 3rd Earl of Effingham following his death in November 1791.

His clemency proved popular with the planters and he won praise for his ‘mildness’ and for maintaining calm after the outbreak of a major slave uprising in nearby St Domingue.

Several of its white colonists sought refuge in Jamaica and requested that Britain take over the French colony. Williamson cultivated these contacts, for St Domingue was a source of enormous wealth. Following the outbreak of war in 1793 he received permission to send troops to those areas that would accept a British protectorate. In September there began a tenuous five-year military occupation. Slave owners welcomed the British forces into much of western and southern St Domingue, and plantation production revived. Ultimately, however, their alliance could make little headway against the burgeoning insurrection among the enslaved and free coloured populations. Troops sent from Europe were vastly outnumbered and died quickly from disease. Yet, in the optimism following the capture of Port-au-Prince on 4 June 1794, Williamson was made a knight of the Bath on 18 November and governor of St Domingue, where he arrived on 26 May 1795.

The governor had to implement an experiment in what later became crown colony government. Reintroducing civil administration into a society torn apart by the French Revolution proved a delicate task. Although Williamson generally had a good word for everyone, his favouring of radical Anglophile colonists over conservative émigrés from France was received badly in Whitehall. The occupation, moreover, became notorious for military losses and escalating costs. Yellow fever, inflation, and the guerrilla warfare of the insurgents doomed the expedition. Williamson expanded the use of black soldiers but was unable to reduce the death rate of British troops. Instructed to foster colonial support for British rule, the humane and generous governor spent lavishly, both his own money and the government's. Since he was fluent in French and fond of late-night drinking and story-telling, he was well liked by wealthy colonists, but, indulgent and overworked, he allowed corruption to flourish around him.

Perceived as a lax administrator and poor judge of men, Williamson was recalled in October 1795; he left the colony on 14 March 1796. His final promotion was as lieutenant-general, on 26 January 1797.

Sir Adam returned to Avebury alone in 1797, for Ann had died of yellow fever whilst they were in Jamaica. Williamson died from the effects of a fall in the dining room/great hall at Avebury on 21 October 1798. It is believed he fractured several ribs in the fall, possibly puncturing a lung. Death would have been slow and painful, his body finally succumbing to respiratory failure.

His obituary in the ‘Gentleman’s Magazine’ of 21 October 1798 reads;

‘At Averbury [sic] House, Wilts, Lieut. Gen. Sir Adam Williamson, K.B. and colonel of the 72nd regiment of foot, and for a short time, governor of Jamaica. His death was occasioned by a violent fall, which fractured two of his ribs, and so terribly bruised him that he languished from Friday till Sunday’.

Source: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited by David P. Geggus. Subsequent edits by Willow

Sir Adam Williamson's funeral hatchments can be found on the south wall of St. James church Avebury. In his will he bequeathed Avebury Manor to Ann’s nephew - Richard Jones.

if no portrait is shown above, see this link

http://aveburymanor.blogspot.com/2012/08/sir-adam-williamson-1733-1798.html

Last edited: