jazzeum

Four Star General

- Joined

- Apr 23, 2005

- Messages

- 38,435

This interesting article was in today's New York Times:

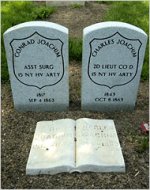

Conrad Joachim, a German immigrant, marched off to war from his home on Greenwich Street in Manhattan on May 13, 1862, enlisting as an assistant surgeon in the 15th New York Heavy Artillery. Charles Joachim, whom historians believe to be his son, had already joined the same unit.

More than 1,200 markers were lined up for a Memorial Day service.

Four months later, Conrad was dead; and in another year, so was Charles, at about the age of 20. They were buried in the same grave at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, beneath a marble headstone that is an exquisitely carved open book inscribed with both their names. But the stone slowly sank into the earth as the centuries turned twice, and the cemetery and the city were completed around them.

The Joachim family’s sacrifice may have been forever lost to history if not for a formidable labor of detective work involving hundreds of volunteers and lasting longer than the Civil War itself. Now the Joachims are among more than 1,200 Civil War soldiers with new gravestones at Green-Wood. And today, for the first time, the cemetery is honoring the full known complement of veterans of the country’s deadliest war.

Dozens of veterans’ descendants, some from as far away as Spain, will be joined at 9 a.m. by volunteers and Civil War re-enactors for a public ceremony. There will be a parade, a color guard, a fife and drum corps, crashing salutes from an artillery battery and speeches of welcome and remembrance. Then, descendants and history lovers will read the names of the veterans.

Over five years, the volunteers have scoured not only Green-Wood’s grounds, but also cemetery records, pension and enlistment archives, government databases, regimental histories, published obituaries and death notices. They have also found and interviewed soldiers’ descendants.

The project identified not 200 Civil War veterans — as had originally been expected — but 2,998. Many gravestones were missing, damaged or obliterated; some, like the Joachims’ marble, had sunk beneath the grass. And so the volunteers filled out more than 1,200 applications for new markers, since the Department of Veterans Affairs supplies them if originals are unreadable or lost.

“This is a work of historical rescue,” said one of the volunteers, Jeffrey Blustein, a medical ethicist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx. “History isn’t just about the rich and famous, it’s about all the forgotten people, ordinary people who otherwise would never be known.”

The Joachims’ original gravestone was discovered after their new ones had already been ordered; now the elegant marble stone, earth-tinged from decades in the ground, contrasts with the gleaming granite of the new markers.

Most of the new stones have yet to be installed, and are lined up in a meadow, evoking not so much Brooklyn as Arlington, Gettysburg or Colleville-sur-Mer.

The effort began in 2002, with the restoration and rededication of the massive 1869 Civil War Soldiers’ Monument on the cemetery’s promontory, Battle Hill, bringing together dozens of volunteers. “We discussed it and came to a conclusion: Let’s see if we can find all the Civil War dead at Green-Wood,” said Jeff Richman, the cemetery’s historian.

Soon, volunteers were walking every inch of Green-Wood. One of them, Marge Raymond, found the grave of Capt. Henry Augustus Sand, and later located one of his descendants in Germany, found transcripts of the captain’s letters and even a photograph.

She learned that he served with the 103d New York Infantry and was fatally wounded by a cannonball on Sept. 17, 1862, at the Battle of Antietam, when he seized the flag of a fallen color-bearer and urged his men forward. He died six weeks later. “He made a major contribution to our country,” Ms. Raymond said, “but his stone was covered in algae and dirt, and we had to clean it before we could read it.”

Mr. Richman directed the group in a search of online databases, looking for troops raised in Brooklyn or Manhattan. In the end, volunteers amassed about 162,000 names of potential veterans, and compared them with those in some 60 “chronology books,” historic 22-by-16-inch Green-Wood burial ledgers inscribed in spidery script that listed causes of death, but not veteran status. “If someone died in 1902, their military service might not have been viewed by then as being particularly significant,” Mr. Richman said.

After the comparison, he said, “we got 5,000 hits, but we had no idea whether the names were coincidental, or whether they were real matches with real soldiers.”

So volunteers calculated the relative ages of possible soldiers from dates of birth and compared those with the ages in the cemetery records. Then they sought the names in regimental histories, death notices, obituaries and other historical resources.

“We became very protective of them, very personal and emotional about them,” said Susan Tomasi, a Brooklyn school psychologist.

Whole families joined the quest. Stephanie Carey of Somerset, N.J., who has long been proud that one of her ancestors served in the Civil War, was assisted by her husband, Mark, an electrical engineer, and her daughter, Victoria, a high-school senior.

“There were so many great but forgotten sacrifices, like the Union doctor who was captured in the South, and though he could have been returned to the North, chose to stay down there to take care of his troops,” said Laura Congleton, a genealogist from Brooklyn. Her great-great-grandfather, Johnson Foster, died at the Andersonville prison in Georgia and was buried there.

As word spread about the project, volunteers began hearing from descendants as far away as England, Germany and Spain; many sent in pictures, biographical information and “sometimes the original commissions or discharge papers,” Mr. Richman said.

Many grave markers were believed to be missing until a team of cemetery workers began using metal rods to probe the greens. “We found stone after stone that had sunk below the grass line,” Mr. Richman said. “The gravestones make a pinging sound.”

Some of the veterans’ families were most likely unable to afford headstones; others chose marble or limestone, which have eroded because of age and acid rain. “After researching their lives, it gives you a lump in your throat to see their names on the new stones from the V.A.,” Ms. Tomasi said.

In what the cemetery calls the Soldiers’ Lot — a plot on less than an acre donated in 1863 by Green-Wood primarily for those who died in battle or from disease and could not afford grand burial monuments like the ones around them — some of the new granite stones, being installed at Green-Wood’s expense, have been set up next to the soldiers’ original markers.

Conrad and Charles Joachim were buried there. Only 28 feet away, adjacent to the plot — which was restricted to veterans — researchers discovered the gravestone of Conrad Joachim’s wife, Eliza, who died in 1896, 34 years after her husband.

One volunteer, Barbara Farley, a widow whose husband’s great-grandfather was a Civil War veteran, discovered that one of those buried in Green-Wood, Robert Mitchell, had lived at 5712 14th Avenue in Brooklyn. That was just around the corner from the house where Ms. Farley grew up, at 1364 57th Street.

“As a child, I might have played with his descendants,” said Ms. Farley, a retired neurobiologist from Brooklyn. Despite intensive research, she has found little of his biography, save that he died in 1913.

Mr. Richman’s book on the project, “Final Camping Ground: Civil War Veterans at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, in Their Own Words,” will be available at Green-Wood today and is accompanied by an illustrated collection of the veterans’ biographies on compact disc.

He has not given up the search. “We think we’ve found less than 50 percent of the veterans, so far,” Mr. Richman said.

Many of the stones bear a black carved shield that traditionally marked those of the Union dead; Confederate soldiers have their own symbol, which Mr. Richman said was a cross and a wreath. Some who fought for the South were buried at Green-Wood because they were included in the family plots of Yankee relatives, he said. On a recent afternoon a new stone was being carefully placed in the Soldiers’ Lot by two gravediggers, Felix Hernandez and Elvis Merizalde.

“It’s an honor to be involved in this job,” said George Barreto, a foreman in the grave department. “We are giving them the honor they deserve.” Among Green-Wood’s nearly 600,000 graves and manicured hills offering panoramic views of New York Harbor are veterans from every American war, said Richard J. Moylan, Green-Wood’s president.

Mr. Moylan said the four veterans of the Iraq war buried in Green-Wood — Joseph O. Behnke, Manny Hornedo, Angel R. Ramirez and Michael D. Rivera — have also been joined by Steven C. Vincent, a journalist from New York who was abducted and killed in Iraq in 2005.

The Civil War project has inspired the cemetery to begin similar efforts for veterans from “the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Spanish-American War, the world wars, Korea and Vietnam,” he said.

“We even have a veteran who won the Medal of Honor in the Boxer Rebellion,” he said, referring to China’s antiforeign movement in 1900. “This is just the beginning of a process of reconnecting with the history of our cemetery — and the history of our country.”

Conrad Joachim, a German immigrant, marched off to war from his home on Greenwich Street in Manhattan on May 13, 1862, enlisting as an assistant surgeon in the 15th New York Heavy Artillery. Charles Joachim, whom historians believe to be his son, had already joined the same unit.

More than 1,200 markers were lined up for a Memorial Day service.

Four months later, Conrad was dead; and in another year, so was Charles, at about the age of 20. They were buried in the same grave at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, beneath a marble headstone that is an exquisitely carved open book inscribed with both their names. But the stone slowly sank into the earth as the centuries turned twice, and the cemetery and the city were completed around them.

The Joachim family’s sacrifice may have been forever lost to history if not for a formidable labor of detective work involving hundreds of volunteers and lasting longer than the Civil War itself. Now the Joachims are among more than 1,200 Civil War soldiers with new gravestones at Green-Wood. And today, for the first time, the cemetery is honoring the full known complement of veterans of the country’s deadliest war.

Dozens of veterans’ descendants, some from as far away as Spain, will be joined at 9 a.m. by volunteers and Civil War re-enactors for a public ceremony. There will be a parade, a color guard, a fife and drum corps, crashing salutes from an artillery battery and speeches of welcome and remembrance. Then, descendants and history lovers will read the names of the veterans.

Over five years, the volunteers have scoured not only Green-Wood’s grounds, but also cemetery records, pension and enlistment archives, government databases, regimental histories, published obituaries and death notices. They have also found and interviewed soldiers’ descendants.

The project identified not 200 Civil War veterans — as had originally been expected — but 2,998. Many gravestones were missing, damaged or obliterated; some, like the Joachims’ marble, had sunk beneath the grass. And so the volunteers filled out more than 1,200 applications for new markers, since the Department of Veterans Affairs supplies them if originals are unreadable or lost.

“This is a work of historical rescue,” said one of the volunteers, Jeffrey Blustein, a medical ethicist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx. “History isn’t just about the rich and famous, it’s about all the forgotten people, ordinary people who otherwise would never be known.”

The Joachims’ original gravestone was discovered after their new ones had already been ordered; now the elegant marble stone, earth-tinged from decades in the ground, contrasts with the gleaming granite of the new markers.

Most of the new stones have yet to be installed, and are lined up in a meadow, evoking not so much Brooklyn as Arlington, Gettysburg or Colleville-sur-Mer.

The effort began in 2002, with the restoration and rededication of the massive 1869 Civil War Soldiers’ Monument on the cemetery’s promontory, Battle Hill, bringing together dozens of volunteers. “We discussed it and came to a conclusion: Let’s see if we can find all the Civil War dead at Green-Wood,” said Jeff Richman, the cemetery’s historian.

Soon, volunteers were walking every inch of Green-Wood. One of them, Marge Raymond, found the grave of Capt. Henry Augustus Sand, and later located one of his descendants in Germany, found transcripts of the captain’s letters and even a photograph.

She learned that he served with the 103d New York Infantry and was fatally wounded by a cannonball on Sept. 17, 1862, at the Battle of Antietam, when he seized the flag of a fallen color-bearer and urged his men forward. He died six weeks later. “He made a major contribution to our country,” Ms. Raymond said, “but his stone was covered in algae and dirt, and we had to clean it before we could read it.”

Mr. Richman directed the group in a search of online databases, looking for troops raised in Brooklyn or Manhattan. In the end, volunteers amassed about 162,000 names of potential veterans, and compared them with those in some 60 “chronology books,” historic 22-by-16-inch Green-Wood burial ledgers inscribed in spidery script that listed causes of death, but not veteran status. “If someone died in 1902, their military service might not have been viewed by then as being particularly significant,” Mr. Richman said.

After the comparison, he said, “we got 5,000 hits, but we had no idea whether the names were coincidental, or whether they were real matches with real soldiers.”

So volunteers calculated the relative ages of possible soldiers from dates of birth and compared those with the ages in the cemetery records. Then they sought the names in regimental histories, death notices, obituaries and other historical resources.

“We became very protective of them, very personal and emotional about them,” said Susan Tomasi, a Brooklyn school psychologist.

Whole families joined the quest. Stephanie Carey of Somerset, N.J., who has long been proud that one of her ancestors served in the Civil War, was assisted by her husband, Mark, an electrical engineer, and her daughter, Victoria, a high-school senior.

“There were so many great but forgotten sacrifices, like the Union doctor who was captured in the South, and though he could have been returned to the North, chose to stay down there to take care of his troops,” said Laura Congleton, a genealogist from Brooklyn. Her great-great-grandfather, Johnson Foster, died at the Andersonville prison in Georgia and was buried there.

As word spread about the project, volunteers began hearing from descendants as far away as England, Germany and Spain; many sent in pictures, biographical information and “sometimes the original commissions or discharge papers,” Mr. Richman said.

Many grave markers were believed to be missing until a team of cemetery workers began using metal rods to probe the greens. “We found stone after stone that had sunk below the grass line,” Mr. Richman said. “The gravestones make a pinging sound.”

Some of the veterans’ families were most likely unable to afford headstones; others chose marble or limestone, which have eroded because of age and acid rain. “After researching their lives, it gives you a lump in your throat to see their names on the new stones from the V.A.,” Ms. Tomasi said.

In what the cemetery calls the Soldiers’ Lot — a plot on less than an acre donated in 1863 by Green-Wood primarily for those who died in battle or from disease and could not afford grand burial monuments like the ones around them — some of the new granite stones, being installed at Green-Wood’s expense, have been set up next to the soldiers’ original markers.

Conrad and Charles Joachim were buried there. Only 28 feet away, adjacent to the plot — which was restricted to veterans — researchers discovered the gravestone of Conrad Joachim’s wife, Eliza, who died in 1896, 34 years after her husband.

One volunteer, Barbara Farley, a widow whose husband’s great-grandfather was a Civil War veteran, discovered that one of those buried in Green-Wood, Robert Mitchell, had lived at 5712 14th Avenue in Brooklyn. That was just around the corner from the house where Ms. Farley grew up, at 1364 57th Street.

“As a child, I might have played with his descendants,” said Ms. Farley, a retired neurobiologist from Brooklyn. Despite intensive research, she has found little of his biography, save that he died in 1913.

Mr. Richman’s book on the project, “Final Camping Ground: Civil War Veterans at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, in Their Own Words,” will be available at Green-Wood today and is accompanied by an illustrated collection of the veterans’ biographies on compact disc.

He has not given up the search. “We think we’ve found less than 50 percent of the veterans, so far,” Mr. Richman said.

Many of the stones bear a black carved shield that traditionally marked those of the Union dead; Confederate soldiers have their own symbol, which Mr. Richman said was a cross and a wreath. Some who fought for the South were buried at Green-Wood because they were included in the family plots of Yankee relatives, he said. On a recent afternoon a new stone was being carefully placed in the Soldiers’ Lot by two gravediggers, Felix Hernandez and Elvis Merizalde.

“It’s an honor to be involved in this job,” said George Barreto, a foreman in the grave department. “We are giving them the honor they deserve.” Among Green-Wood’s nearly 600,000 graves and manicured hills offering panoramic views of New York Harbor are veterans from every American war, said Richard J. Moylan, Green-Wood’s president.

Mr. Moylan said the four veterans of the Iraq war buried in Green-Wood — Joseph O. Behnke, Manny Hornedo, Angel R. Ramirez and Michael D. Rivera — have also been joined by Steven C. Vincent, a journalist from New York who was abducted and killed in Iraq in 2005.

The Civil War project has inspired the cemetery to begin similar efforts for veterans from “the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Spanish-American War, the world wars, Korea and Vietnam,” he said.

“We even have a veteran who won the Medal of Honor in the Boxer Rebellion,” he said, referring to China’s antiforeign movement in 1900. “This is just the beginning of a process of reconnecting with the history of our cemetery — and the history of our country.”