Frederick Burnaby: the Bravest Man in England

"I have, unfortunately for my own interests, from my earlier childhood had what my old nurse used to call a most ‘contradictorious’ spirit” - Fred Burnaby

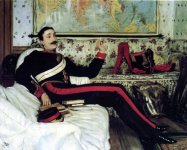

In the Victorian age of larger-than-life heroes, the wildly eccentric colonel towered above the lot of them. He stood 6ft 4ins tall, weighed 15 stone, boasted a 47-inch chest - and had balls to match his enormous frame.

The son of a clergyman, Fred joined the army in 1859 – aged 17 – and quickly became recognised as the strongest man in its ranks. A first-rate boxer, swordsman, rider and runner, his party tricks included vaulting over billiard tables and twisting pokers into knots with his bare hands. He once carried two ponies downstairs at Windsor Castle for a prank, picking one up under each arm like they were cats.

Fred was also into politics. An old-school Tory, he stood for Parliament in 1880 – pitching himself against Joseph Chamberlain in the latter’s Birmingham stronghold.

Chamberlain was one of the bigwigs of the day; Fred never really had a hope. But courage is when you know you’re beaten before you start and you throw yourself into it anyway. Fred was nothing if not courageous – courageous to the point of lunacy most of the time. He lost of course. But by God he gave Chamberlain a run for his money and no one who followed the campaigning in Birmingham that year ever forget Fred Burnaby.

At one meeting in Wolverhampton, for instance, Fred had his stewards bring two persistent hecklers up to the front. He went to the edge of the stage, leaned over and picked them both up by their collars, one in each hand. He then lifted them high for all to see and carried them at arm’s length to the back of the platform where he plonked them in two chairs.

“Sit there, little man. And you, little man, sit there,” he told them in his booming cavalry voice. The crowd was impressed. The heckling stopped. No one was left in any doubt that Colonel Burnaby was not an easy man to intimidate.

One of the most extraordinary men Sudan has ever seen was on the rise at the time. Muhammad Ahmad had gathered around him an army of desert tribesmen and called out for holy war. He was a nineteenth-century Osama bin Laden. He wanted to drive the Egyptians and British out of his country and convert the world to Islam. They called him the Mahdi, “the expected one”. And he wasn’t a man to argue with.

The Mahdi’s followers were a fanatical and ferocious lot. They had God on their side and a terrifyingly impressive record of massacring their enemies. In 1883, a 10,000-strong Egyptian force led by a British officer, William Hicks, was sent against them. It was completely destroyed; just a few hundred men returned alive. Hicks’s head was cut off and taken to the Mahdi.

The following year, Fred – yet again travelling without permission - was among more than 4,000 British troops who had another crack at the rebels at the second battle of El Teb. It was a brutal clash fought at close quarters. And the mighty figure of Fred Burnaby was in the thick of it, doing dire work with a characteristically unorthodox weapon: a double-barrelled shotgun.

Fred used the butt as well both barrels to fearsome effect – a tactic that got his liberal opponents in a lather (killing Arabs with a shotgun: not the done thing at all, old chap). But this time the British won. Fred was mentioned in despatches. He returned home a hero, to most.

The Mahdi army wasn’t finished though. Far from it. Now General Gordon found himself besieged at Khartoum - and, after much dithering, the British government sent a relief expedition under General Wolseley to save him (too late, as things turned out).

Fred, naturally, wanted a piece of the action and Wolseley was happy to have him on board. But bad-boy Burnaby had by now upset so many people at the top his request to go back to the Sudan was turned down.

Who needs permission when you’re Fred Burnaby though? So, true to form, he simply waited for his leave to come around again. Then off he sailed, arriving in Africa against orders and catching up with the British force as it advanced towards Khartoum.

Welcomed by Wolseley, Fred immediately pushed up to the front. When a vanguard of 1,500 British troops ran into about 12,000 Sudanese a few weeks later, he was with them. And it was here, at a dusty desert watering hole called Abu Klea, that his luck finally ran out.

The rebels charged, unexpectedly and ferociously. The British formed into their usual fighting square and fired off a volley. But it failed to check the onslaught and the Mahdists kept coming at them.

The evening before Fred had told the Daily Telegraph’s war correspondent, a Mr Burleigh, he’d left his shotgun behind because of the fuss it’d created when he last used it in battle. Fuss or no fuss, it would have come in handy now.

The Sudanese smashed into the British, piercing their lines in a wild attack. A bloody free-for-all of hacking, slashing and shooting ensued. Burleigh reports seeing Fred riding out, sword in hand, to help a handful of comrades caught stranded outside the square by the sudden charge.

A Mahdi rebel lunged at him with an 8ft spear, but he saw it coming. “Burnaby fenced smartly… and there was a smile on his features as he drove off the man’s awkward points,” writes the Telegraph reporter.

As the struggle continued, a second spearman came up behind Fred and jabbed him in the shoulder. It wasn’t a serious wound but it made him glance back, just for a second. And in that brief moment, the first guy seized his chance and ran his javelin into Fred’s throat.

The force pushed the huge soldier out of his saddle and dumped him on the ground. Burleigh saw what happened next: “Half a dozen Arabs were now about him. With the blood gushing in streams from his gashed throat, the dauntless Guardsman leapt to his feet, sword in hand, and slashed at the ferocious group. They were the wild strokes of a proud, brave man dying hard and he was quickly overborne, and left helpless and dying.”

Dying, but not yet dead. The Mahdi army’s attack ended as swiftly as it started and Fred was still clinging to life when another officer, Lord Binning, found him lying on the ground, his head in the lap of a young private. The lad was crying. “Oh sir,” he said to Binning, “here is the bravest man in England, dying and no one to help him.”

Fred tried to speak but couldn’t. By now, he had a bullet wound in the forehead as well as the hole in his throat. Part of his head had also been cut away. Despite all this, the story goes that Fred died with his familiar smile on his face. Not sure if I believe it, mind. But I want to.

http://greatbritishnutters.blogspot.com/2008/01/frederick-burnaby-bravest-man-in_23.html