jazzeum

Four Star General

- Joined

- Apr 23, 2005

- Messages

- 38,891

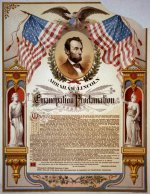

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which was scheduled to come into effect on January 1, 1863.

However, as 1862 drew to a close, the nation’s attention was riveted on whether President Abraham Lincoln would finalize the Emancipation Proclamation. They had little to worry about on that score. In the last days of 1862, Lincoln and his cabinet were not debating whether the administration should go ahead with the proclamation, but fussed over its exact wording. While these details certainly were important, it was clear from the discussions that the Emancipation Proclamation was going ahead.

“Watch Night Meeting”: Slaves await midnight on December 31, 1862

On the morning of January 1, 1863, after an 11 A.M. reception at the White House, he signed the final, official copy of the document, which had been prepared by the State Department. Frederick Seward, the son of Lincoln’s Secretary of State, was an eyewtiness:

At noon, accompanying my father, I carried the broad parchment in a large portfolio under my arm. We, threading our way through the throng in the vicinity of the White House, went upstairs to the President’s room, where Mr. Lincoln speedily joined us. The broad sheet was spread open before him on the Cabinet table. Mr. Lincoln dipped his pen in the ink, and then, holding it a moment above the sheet, seemed to hesitate. Looking around, he said:

“I never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper. But I have been receiving calls and shaking hands since nine o’clock this morning, till my arm is stiff and numb. Now this signature is one that will be closely examined, and if they find my hand trembled they will say ‘he had some compunctions.’ But anyway, it is going to be done.”

So saying, he slowly and carefully wrote his name at the bottom of the proclamation. The signature proved to be unusually clear, bold, and firm, even for him, and a laugh followed at his apprehension. My father, after appending his own name, and causing the great seal to be affixed, had the important document placed among the archives. Copies were at once given to the press.

![ReadingEmancip[1].jpg ReadingEmancip[1].jpg](https://forum.treefrogtreasures.com/data/attachments/90/90232-9e8de87ff156a68df5ebe7abe65489dc.jpg)

A Union soldier reads the proclamation to an enslaved family in this 1864 engraving by J.W. Watts

Some, such as the late great historian Richard Hofstadter, said that the Proclamation had all the majesty of a bill of lading as it was written in precise legal language. However, at the end of the Proclamation, President Lincoln wrote, in part, "I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons."

One effect of the Proclamation was to make possible the use of African Americans as Union troops. In a famous 1864 letter Lincoln said, in part, after his proposal for compensated emancipation was rejected by the border states:

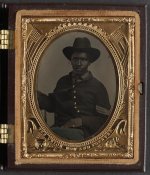

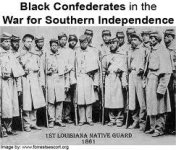

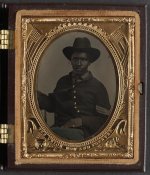

The USCT (United States Colored Troops) became a significant part of the Union Army and without it the war might not have been won. Here we see members of the USCT whose role was made possible by the Emancipation Proclamation. Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress.

However, as 1862 drew to a close, the nation’s attention was riveted on whether President Abraham Lincoln would finalize the Emancipation Proclamation. They had little to worry about on that score. In the last days of 1862, Lincoln and his cabinet were not debating whether the administration should go ahead with the proclamation, but fussed over its exact wording. While these details certainly were important, it was clear from the discussions that the Emancipation Proclamation was going ahead.

“Watch Night Meeting”: Slaves await midnight on December 31, 1862

On the morning of January 1, 1863, after an 11 A.M. reception at the White House, he signed the final, official copy of the document, which had been prepared by the State Department. Frederick Seward, the son of Lincoln’s Secretary of State, was an eyewtiness:

At noon, accompanying my father, I carried the broad parchment in a large portfolio under my arm. We, threading our way through the throng in the vicinity of the White House, went upstairs to the President’s room, where Mr. Lincoln speedily joined us. The broad sheet was spread open before him on the Cabinet table. Mr. Lincoln dipped his pen in the ink, and then, holding it a moment above the sheet, seemed to hesitate. Looking around, he said:

“I never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper. But I have been receiving calls and shaking hands since nine o’clock this morning, till my arm is stiff and numb. Now this signature is one that will be closely examined, and if they find my hand trembled they will say ‘he had some compunctions.’ But anyway, it is going to be done.”

So saying, he slowly and carefully wrote his name at the bottom of the proclamation. The signature proved to be unusually clear, bold, and firm, even for him, and a laugh followed at his apprehension. My father, after appending his own name, and causing the great seal to be affixed, had the important document placed among the archives. Copies were at once given to the press.

![ReadingEmancip[1].jpg ReadingEmancip[1].jpg](https://forum.treefrogtreasures.com/data/attachments/90/90232-9e8de87ff156a68df5ebe7abe65489dc.jpg)

A Union soldier reads the proclamation to an enslaved family in this 1864 engraving by J.W. Watts

Some, such as the late great historian Richard Hofstadter, said that the Proclamation had all the majesty of a bill of lading as it was written in precise legal language. However, at the end of the Proclamation, President Lincoln wrote, in part, "I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons."

One effect of the Proclamation was to make possible the use of African Americans as Union troops. In a famous 1864 letter Lincoln said, in part, after his proposal for compensated emancipation was rejected by the border states:

I was, in my best judgment, driven to the alternative of either surrendering the Union, and with it, the Constitution, or of laying strong hand upon the colored element. I chose the latter.

The USCT (United States Colored Troops) became a significant part of the Union Army and without it the war might not have been won. Here we see members of the USCT whose role was made possible by the Emancipation Proclamation. Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress.