- Joined

- Feb 2, 2011

- Messages

- 2,328

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY COLLECTION

THE RAID ON ST. FRANCIS 1759

ROGER’S RANGERS

Roger’s Rangers was a company of soldiers form the Province of New Hampshire

raised by Major Robert Rogers and attached to the British Army during the Seven Year’s War (French and Indian War).

The unit was quickly adopted into the New England Colonies army as an independent ranger company. Rogers was inspired by colonial Frontiersman Ranger groups across North America and the teachings of unconventional warfare from Ranger such as Benjamin Church.

Robert Rogers trained and commanded his own rapidly deployable light infantry force , which was tasked mainly with reconnaissance as well as conducting special operations against distant targets.Their tactics were built on earlier Colonial precedents and were codified for the first time by Rogers as his 28 “Rules of Ranging”.

RR-34

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY COLLECTION

THE RAID ON ST. FRANCIS 1759,

ROGER’S RANGERS

The tactics proved remarkably effective, so much so that the initial company was expanded into a ranging corps of more than a dozen companies(containing as many as 1,200-1,400 men at its peak). The ranger corps became the chief scouting arm of British Crown forces by the late 1750s.The British forces in America valued Roger’s Rangers for their ability to gather intelligence about the enemy.They were disbanded in 1761.

RR-34D

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY COLLECTION

THE RAID ON ST. FRANCIS 1759,

ROGER’S RANGERS

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

THE BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL, 17th JUNE 1775.

THE buttAULT ON THE REDOUBT AT BREED’S HILL

Boston was the third largest town in North America, and stood on a Peninsula connected to the mainland by a neck just wide enough to cross at high tide. The harbour, large enough to be strategically significant, and central to the town’s economy, was formed by a chain of islands stretching out to sea, guarded by reefs and ledges.

North west of Boston was Charlestown, a largely rural peninsula one and a half miles long. Charlestown stood at the south east corner with three hills behind it. Bunker’s Hill, nearest the neck of the Peninsula, Breed’s Hill 200 yards above the town and Moulton’s Hill to the north east.

On the 16th June 1775, 3 detachments from Massachusetts regiments under the command of Colonel William Prescott and engineer Captain Richard Gridley, crossed the Charlestown neck and arrived at Bunker Hill.

Captain Richard Gridley and Prescott disagreed as to where they should locate their defense. Some work was performed on Bunker Hill, but Breed’s Hill was closer to Boston and viewed as being more defensible, and they decided to build their primary redoubt there.

Prescott and his men began digging a square fortification about 130 ft a side with ditches and earthen walls. The walls of the redoubt were about 6 feet high.

Work began at midnight, and around 4am one of the British warships spotted the earthworks on Breed’s Hill and opened fire.

The British command agreed that the works posed a significant threat, but were at this time sufficiently incomplete and isolated to offer a chance of a successful attack.

The original British plan was to bypass the redoubt to the north and capture Bunker’s Hill and the neck of the peninsula, thus isolating the redoubt on Breed’s Hill.

The Americans repulsed two British buttaults, with significant British casualties. The British captured the redoubt on their third buttault, after the defenders had run out of ammunition. The colonists retreated over Bunker Hill, leaving the British finally in control of the Peninsula.

The battle was a tactical victory for the British, but it proved to be a sobering experience for them; they incurred many more casualties than the Americans had sustained, including many officers. The battle had demonstrated that inexperienced militia were able to stand up to regular army troops in battle. Subsequently, the battle discouraged the British from any further frontal attacks against well defended front lines. American casualties were much fewer, although their losses included General Joseph Warren, and Major Andrew McClary, the final casualty of the battle.

BRITISH MARINES

The Marines, which only became “Royal Marines” in 1802, were the Royal Navy’s private army, administered by the Admiralty and controlled by senior naval officers. The rank and file were volunteers and wore army style uniforms and equipment. However they were trained to serve on warships and undertake amphibious operations. The 50 companies, shared between Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth, were not regimented, and detachments, or in some cases individual replacements were buttigned on an ad hoc basis.

The first Marines sent to Boston were to form a battalion of 600 men under Major Pitcairn, but by March only 336 were present, as they soon became an object of inter service rivalry over pay, food and conditions. Although initially physically inferior to their army comrades, and short of essential equipment for service on land, incessant drilling and regular marches into the countryside soon created a fine unit.

Another group of over 700 men arrived in May, and the whole force formed two battalions, with grenadier and light companies.

The 1st and 2nd Marines were to play an important part in the buttault on the southern defences of the Breed’s Hill redoubt.

MBHL-23

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

THE BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL, JUNE 17th 1775,

THE buttAULT ON THE REDOUBT AT BREED’S HILL,

BRITISH MARINES,

DRUMMER

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

THE RHODE ISLAND TRAIN OF ARTILLERY 1775

The Rhode Island Train of Artillery, also known as the United Train of Artillery, was a significant unit in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.

The unit was formed in 1775 and played a crucial role in the early battles of the war.

The unit was reorganized and expanded to include additional companies, contributing to the overall strength of the Continental Army.

The unit was involved in various campaigns, including the New York and New Jersey Campaigns, and was instrumental in the Siege of Boston.

RIART-01

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

THE RHODE ISLAND TRAIN OF ARTILLERY 1775,

2 ARTILLERY CREW

The reorganization and expansion of the Rhode Island Militia in 1774 included the formation of two new volunteer companies, the Providence Train of Artillery and the Providence Fusiliers.

In April 1775, these were combined to form “The United Company of the Train of Artillery of the Town of Providence”, thereafter usually termed “The United Train of Artillery”.

Commanded by Major John Crane, it was buttigned to the Rhode Island Brigade, which Brigadier General Nathanael Greene led to join the American forces besieging Boston.

Crane was sometimes referred to as “Captain” and the unit as “Crane’s Company”.

During the reorganization of the American Army in January 1776, the United Train, or rather those of its men who would re-enlist, were absorbed into Knox’s Massachusetts Artillery Regiment (formerly Colonel Richard Gridley’s), with Crane becoming the latter unit’s “first major”.

The Rhode Island Train of Artillery’s uniform and equipment were notable for their distinctive features, such as the brown faced red coats and leather caps with gold painted anchors.

Like many other American regiments at the beginning of the war, the United Train wore brown coats. Its facings were red, its buttons brass and were stamped with the Rhode Island’s anchor device.

Waistcoat and breeches were white linen, and enlisted men wore short black gaiters.

RIART-02N

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

THE RHODE ISLAND TRAIN OF ARTILLERY 1775,

4 ARTILLERY CREW

The Train’s headgear was unique, a cap made of six triangular pieces of jacked leather with a small red and brown tuft at the crown.

To this was attached a frontal piece whose odd shape may have been inspired by the classic Phrygian or “liberty” cap. Above the Rhode Island anchor motive in the centre is a red scroll with the words “For Our Country” in silver letters.

Below the anchor on a gold scroll is the black lettered motto “In Te Domine Speramus”, (In Thee Lord Is Our Hope).

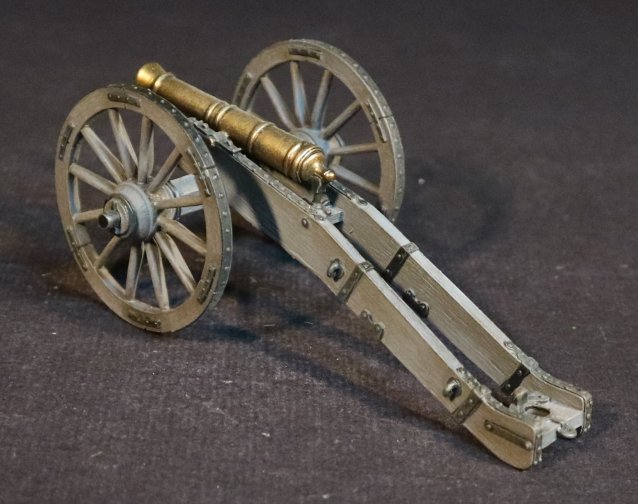

The cannon used in the Revolution by all armies was the standard smooth-bore muzzle-loading gun which had been little changed in the previous two hundred years and which would serve as the principal artillery weapon of most of the worlds armies for another hundred. They were cast of iron or bronze; loaded with a prepared cartridge of paper or cloth containing gunpowder, followed by a projectile. It was fired by igniting a goose-quill tube containing gunpowder, or “quickmatch,” inserted into a vent-hole that communicated with the charge in the gun; and when fired, the recoil threw it backward, necessitating it being wrestled back into the firing position by the gun crew.

AWIGUN01

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

AMERICAN ARTILLERY,

6 pdr FIELD GUN

AWIGUN02

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

AMERICAN ARTILLERY,

6 pdr FIELD GUN

The main field pieces in the war were the 3-pound galloper and the steady 6-pound field piece.

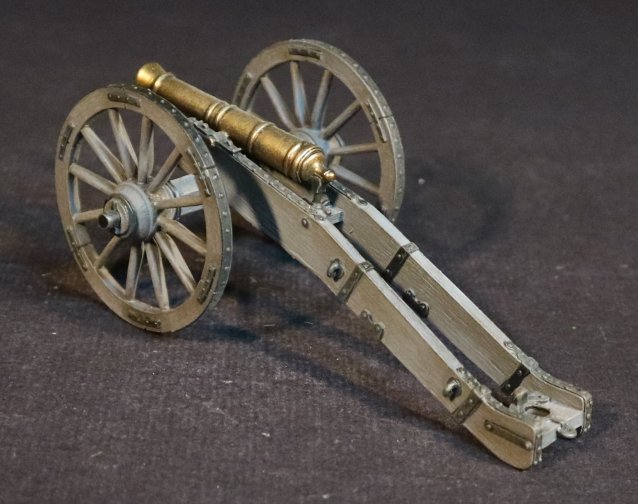

AWIGUN03

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

BRITISH ARTILLERY,

6 pdr FIELD GUN

Iron guns were stronger and therefore could withstand bigger charges of gunpowder; most recommendations for the loading of iron cannon called for a powder charge of one-third the weight of the round shot for the gun. The recommendation for bronze guns was restricted to a charge of only one-quarter of the shot weight. Thus, iron guns could usually achieve a greater range than their equivalent in bronze; an iron six-pounder could fire 1500 yards, while a bronze six-pounder could do 1200 yards.

The advantage of bronze guns was that they were much lighter than their iron equivalents of the same caliber, so that bronze guns were preferred for campaigning, even though the range was less, since they could be moved more easily.

Another advantage of bronze ordnance was that when, eventually, the gun was so worn as to be unserviceable, it could be melted down and recast; whereas an iron gun could only be scrapped.

Last but not least, when cannon were lost at sea, bronze guns were salvagable and almost immediately re-usable, whereas even a short time immersed in sea-water was enough to destroy an iron cannon’s usefulness.

British forces used both bronze and iron artillery pieces, and within each caliber group there were generally a number of variant models. This was simply due to the incredibly long useful life span of a muzzle loading cannon.

**PLEASE CONTACT YOUR LOCAL DEALER TO PLACE YOUR PRE-ORDERS**

THE RAID ON ST. FRANCIS 1759

ROGER’S RANGERS

Roger’s Rangers was a company of soldiers form the Province of New Hampshire

raised by Major Robert Rogers and attached to the British Army during the Seven Year’s War (French and Indian War).

The unit was quickly adopted into the New England Colonies army as an independent ranger company. Rogers was inspired by colonial Frontiersman Ranger groups across North America and the teachings of unconventional warfare from Ranger such as Benjamin Church.

Robert Rogers trained and commanded his own rapidly deployable light infantry force , which was tasked mainly with reconnaissance as well as conducting special operations against distant targets.Their tactics were built on earlier Colonial precedents and were codified for the first time by Rogers as his 28 “Rules of Ranging”.

RR-34

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY COLLECTION

THE RAID ON ST. FRANCIS 1759,

ROGER’S RANGERS

The tactics proved remarkably effective, so much so that the initial company was expanded into a ranging corps of more than a dozen companies(containing as many as 1,200-1,400 men at its peak). The ranger corps became the chief scouting arm of British Crown forces by the late 1750s.The British forces in America valued Roger’s Rangers for their ability to gather intelligence about the enemy.They were disbanded in 1761.

RR-34D

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY COLLECTION

THE RAID ON ST. FRANCIS 1759,

ROGER’S RANGERS

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

THE BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL, 17th JUNE 1775.

THE buttAULT ON THE REDOUBT AT BREED’S HILL

Boston was the third largest town in North America, and stood on a Peninsula connected to the mainland by a neck just wide enough to cross at high tide. The harbour, large enough to be strategically significant, and central to the town’s economy, was formed by a chain of islands stretching out to sea, guarded by reefs and ledges.

North west of Boston was Charlestown, a largely rural peninsula one and a half miles long. Charlestown stood at the south east corner with three hills behind it. Bunker’s Hill, nearest the neck of the Peninsula, Breed’s Hill 200 yards above the town and Moulton’s Hill to the north east.

On the 16th June 1775, 3 detachments from Massachusetts regiments under the command of Colonel William Prescott and engineer Captain Richard Gridley, crossed the Charlestown neck and arrived at Bunker Hill.

Captain Richard Gridley and Prescott disagreed as to where they should locate their defense. Some work was performed on Bunker Hill, but Breed’s Hill was closer to Boston and viewed as being more defensible, and they decided to build their primary redoubt there.

Prescott and his men began digging a square fortification about 130 ft a side with ditches and earthen walls. The walls of the redoubt were about 6 feet high.

Work began at midnight, and around 4am one of the British warships spotted the earthworks on Breed’s Hill and opened fire.

The British command agreed that the works posed a significant threat, but were at this time sufficiently incomplete and isolated to offer a chance of a successful attack.

The original British plan was to bypass the redoubt to the north and capture Bunker’s Hill and the neck of the peninsula, thus isolating the redoubt on Breed’s Hill.

The Americans repulsed two British buttaults, with significant British casualties. The British captured the redoubt on their third buttault, after the defenders had run out of ammunition. The colonists retreated over Bunker Hill, leaving the British finally in control of the Peninsula.

The battle was a tactical victory for the British, but it proved to be a sobering experience for them; they incurred many more casualties than the Americans had sustained, including many officers. The battle had demonstrated that inexperienced militia were able to stand up to regular army troops in battle. Subsequently, the battle discouraged the British from any further frontal attacks against well defended front lines. American casualties were much fewer, although their losses included General Joseph Warren, and Major Andrew McClary, the final casualty of the battle.

BRITISH MARINES

The Marines, which only became “Royal Marines” in 1802, were the Royal Navy’s private army, administered by the Admiralty and controlled by senior naval officers. The rank and file were volunteers and wore army style uniforms and equipment. However they were trained to serve on warships and undertake amphibious operations. The 50 companies, shared between Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth, were not regimented, and detachments, or in some cases individual replacements were buttigned on an ad hoc basis.

The first Marines sent to Boston were to form a battalion of 600 men under Major Pitcairn, but by March only 336 were present, as they soon became an object of inter service rivalry over pay, food and conditions. Although initially physically inferior to their army comrades, and short of essential equipment for service on land, incessant drilling and regular marches into the countryside soon created a fine unit.

Another group of over 700 men arrived in May, and the whole force formed two battalions, with grenadier and light companies.

The 1st and 2nd Marines were to play an important part in the buttault on the southern defences of the Breed’s Hill redoubt.

MBHL-23

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

THE BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL, JUNE 17th 1775,

THE buttAULT ON THE REDOUBT AT BREED’S HILL,

BRITISH MARINES,

DRUMMER

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

THE RHODE ISLAND TRAIN OF ARTILLERY 1775

The Rhode Island Train of Artillery, also known as the United Train of Artillery, was a significant unit in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.

The unit was formed in 1775 and played a crucial role in the early battles of the war.

The unit was reorganized and expanded to include additional companies, contributing to the overall strength of the Continental Army.

The unit was involved in various campaigns, including the New York and New Jersey Campaigns, and was instrumental in the Siege of Boston.

RIART-01

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

THE RHODE ISLAND TRAIN OF ARTILLERY 1775,

2 ARTILLERY CREW

The reorganization and expansion of the Rhode Island Militia in 1774 included the formation of two new volunteer companies, the Providence Train of Artillery and the Providence Fusiliers.

In April 1775, these were combined to form “The United Company of the Train of Artillery of the Town of Providence”, thereafter usually termed “The United Train of Artillery”.

Commanded by Major John Crane, it was buttigned to the Rhode Island Brigade, which Brigadier General Nathanael Greene led to join the American forces besieging Boston.

Crane was sometimes referred to as “Captain” and the unit as “Crane’s Company”.

During the reorganization of the American Army in January 1776, the United Train, or rather those of its men who would re-enlist, were absorbed into Knox’s Massachusetts Artillery Regiment (formerly Colonel Richard Gridley’s), with Crane becoming the latter unit’s “first major”.

The Rhode Island Train of Artillery’s uniform and equipment were notable for their distinctive features, such as the brown faced red coats and leather caps with gold painted anchors.

Like many other American regiments at the beginning of the war, the United Train wore brown coats. Its facings were red, its buttons brass and were stamped with the Rhode Island’s anchor device.

Waistcoat and breeches were white linen, and enlisted men wore short black gaiters.

RIART-02N

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

THE RHODE ISLAND TRAIN OF ARTILLERY 1775,

4 ARTILLERY CREW

The Train’s headgear was unique, a cap made of six triangular pieces of jacked leather with a small red and brown tuft at the crown.

To this was attached a frontal piece whose odd shape may have been inspired by the classic Phrygian or “liberty” cap. Above the Rhode Island anchor motive in the centre is a red scroll with the words “For Our Country” in silver letters.

Below the anchor on a gold scroll is the black lettered motto “In Te Domine Speramus”, (In Thee Lord Is Our Hope).

The cannon used in the Revolution by all armies was the standard smooth-bore muzzle-loading gun which had been little changed in the previous two hundred years and which would serve as the principal artillery weapon of most of the worlds armies for another hundred. They were cast of iron or bronze; loaded with a prepared cartridge of paper or cloth containing gunpowder, followed by a projectile. It was fired by igniting a goose-quill tube containing gunpowder, or “quickmatch,” inserted into a vent-hole that communicated with the charge in the gun; and when fired, the recoil threw it backward, necessitating it being wrestled back into the firing position by the gun crew.

AWIGUN01

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

AMERICAN ARTILLERY,

6 pdr FIELD GUN

AWIGUN02

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

AMERICAN ARTILLERY,

6 pdr FIELD GUN

The main field pieces in the war were the 3-pound galloper and the steady 6-pound field piece.

AWIGUN03

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775-1783,

BRITISH ARTILLERY,

6 pdr FIELD GUN

Iron guns were stronger and therefore could withstand bigger charges of gunpowder; most recommendations for the loading of iron cannon called for a powder charge of one-third the weight of the round shot for the gun. The recommendation for bronze guns was restricted to a charge of only one-quarter of the shot weight. Thus, iron guns could usually achieve a greater range than their equivalent in bronze; an iron six-pounder could fire 1500 yards, while a bronze six-pounder could do 1200 yards.

The advantage of bronze guns was that they were much lighter than their iron equivalents of the same caliber, so that bronze guns were preferred for campaigning, even though the range was less, since they could be moved more easily.

Another advantage of bronze ordnance was that when, eventually, the gun was so worn as to be unserviceable, it could be melted down and recast; whereas an iron gun could only be scrapped.

Last but not least, when cannon were lost at sea, bronze guns were salvagable and almost immediately re-usable, whereas even a short time immersed in sea-water was enough to destroy an iron cannon’s usefulness.

British forces used both bronze and iron artillery pieces, and within each caliber group there were generally a number of variant models. This was simply due to the incredibly long useful life span of a muzzle loading cannon.

**PLEASE CONTACT YOUR LOCAL DEALER TO PLACE YOUR PRE-ORDERS**