Part 17B2 Byronism, Freedom and the Greek War of Independence of the 1820s

"I had had a taste of freedom"

Winslow Homer 1878

The last time we saw Lord Byron, he was aboard the USS Constitution off the coast of Leghorn, Italy in May of 1822. In this segment we shall consider Byron's involvement in the Greek War of Independence. Byron's participation in the cause of Greek freedom should be viewed as a transnational event involving the United States as well as Europe. It also provided a precedent for the later actions of Giuseppe Garibaldi and ultimately the Italian Risorgimento. In fact there are similarities between Garibaldi and Lord Byron. Both men were products of the age of Romanticism and hero worship. As I have noted previously, the swashbuckling heroic male adventurer was a mainstay of the movement.

The phenomenon of "Byronism" was an international phenomenon. We saw this previously in the enthusiastic reception he received from the officers aboard the USS Constitution. Garibaldi's mentor and leading figure of the Risorgimento, Giuseppe Mazzini, the Italian revolutionary was deeply influenced by Byronism.

The 1822 visit of Byron aboard the USS Constitution may be seen as a symbolic event about freedom and America. When the ship was launched in 1797, President George Washington, named it after America's most important document since the Declaration of Independence. Its Bill of Rights put forth the new nation's ten basic freedoms. Indeed the ship was an embodiment of the protection of those freedoms on the high seas, showing the flag and protecting the nation's trade and commerce around the world, initially in the Quasi War with France (1798-1800) and during the First Barbary War (1801-1805).

In the year prior to his visit aboard the ship, Byron had described that aspect of the United States on October 12, 1821 when he wrote : "America is a Model of

force and freedom & moderation..."

The Greek War of Independence (1821-1832) should be viewed in the context of transnational history. It is related to the three Atlantic Revolutions and national struggles for freedom during the 18th Century: the American Revolution of 1776, the French Revolution of 1789, and the Haitian Revolution of 1791-1804. The latter was the largest successful slave rebellion in the Western Hemisphere.

The Greek War or Revolution was about resistance to the oppression of the Turks of the Ottoman Empire who had controlled Greece since 1453. Between 1809 and 1811 Byron went on The Grand Tour. However, due to the contemporary Napoleonic Wars, Byron had to detour away from the usual itinerary and headed for the Mediterranean and Aegean Sea, ultimately touring Greece, where he got his first hand view of the structures of the Ancient Greeks and their civilization's role in the development of Democracy and its concomitant freedoms. While there, Byron became aware of the plight of the Greeks under Ottoman rule and the loss of their heritage of Greek culture. Among the outcomes of Byron's 1809 visit to Greece was the publication of his poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage issued in four Cantos between 1812 and 1818. Parts of the poem are set in the Greece he had recently visited. It's publication made him well known throughout Europe and North America. This was among the poems that was familiar to the officers he had met aboard the USS Constitution in 1822.

The Greek War for Independence received wide coverage in the Western press and inspired individuals to travel to Greece to join the effort. Byron was among them. In his response to the war and the Greek need for fighters, he was characteristic of the Romantic movement's love of the dashing hero going off to battle in exotic lands. The combination of Greece and the Ottoman Turks fit the criteria perfectly. In that respect, he foreshadows Garibaldi who in his early years offered his services to several Latin American revolutions.

Byron's military volunteerism was foreshadowed by a poem he wrote in 1820, one year before the Greek War began.

When a Man Hath No Freedom(1820)

By George Gordon, Lord Byron

"When a man hath no freedom to fight for at home,

Let him combat for that of his neighbours;

Let him think of the glories of Greece and of Rome,

And get knocked on the head for his labours,

To do good to mankind is the chivalrous plan,

And is always as nobly requited;

Then battle for freedom wherever you can,

And if not shot or hanged you’ll get knighted."

Greek resistance to Turkish control began in earnest in 1821. Secret revolutionary societies had been organizing throughout Greece, providing a

basis for their rebellion. News of the uprising spread rapidly to the nations of Western Europe and North America. Interest in Greece and its important heritage had already become prevalent among artists, writers and intellectuals during the Romantic movement of Panhellenic Societies (lovers of all things Greek) in Europe and North America. Members were inspired by the Ancient Greek democratic ideals of freedom, liberty, and equality. It was in such a context that Byron would become involved in the Greek struggle.

On July 15, 1823 Byron set sail for Greece with stops along the way to gather funds and supplies for the Greeks. He landed at Missolonghi on January 4, 1824. In 1861Greek artist Theodoros Vryzakis reconstructed Byron's arrival in an oil painting entitled The Reception of Lord Byron at Missolonghi. Byron is standing in the center of the painting surrounded by Greek soldiers and dignitaries of the local Greek Orthodox Church who are grateful for his efforts on their behalf. Unfortunately, Byron's time in Greece would be cut short by his death on April 19 when he died in his sleep. Ten days earlier he got caught in a heavy rain while out on horseback riding and eventually succumbed to a fatal fever. His death made headlines around the world and enhanced his fame and reputation as an archetypal hero of the Romantic Era. The phenomenon of Byronism inspired more volunteers to come to the aid of the Greeks. Byronism may be seen as a predecessor to Garibaldi-Mania.

Missolonghi later came under multiple sieges by the Turks and became an icon of the sufferings of the Greek people at the hands of the Ottomans. The Third Siege of 1826 resulted in the massacre of the Greek population. Many of them died within the walls of the city after the failure of an escape plan on April 19, 1826. While others were captured and sold as slaves. The 19th Century French Romantic painter Eugene Delacroix produced two of the most famous paintings of the Greek War. The first was completed in 1824. Entitled The Massacre at Chios it records an event from April 1822 when Ottoman forces descended upon the island of Chios and massacred or enslaved the Greek residents of the island.

Delacroix' second painting represents the massacre that occurred at Missolonghi in 1826. Painted in the same year, Greece shows a woman dressed in blue and white (the colors of the Greek flag) kneeling upon the rubble of the destroyed city. Directly beneath her is a man's arm projecting out from under the rubble where his body has been entrapped. His arm is draped over the barrel of a cannon. To the right behind the woman is a triumphant Ottoman warrior holding a spear. His clothing and African appearance suggests that he was one of the Egyptian soldiers brought to Greece to supplement the forces of the Ottoman army. Delacroix meant the woman to be an allegory of Greece. "She" will ultimately survive and be victorious over the Ottoman Empire. When these two paintings were displayed in Paris, they inspired more French Philhellenes to travel to Greece to help.

Delacroix had not traveled to Greece to do his paintings. They were painted in his Parisian studio. However, he did gather newspaper accounts and eyewitness reports to give his paintings a feeling of authenticity.The painter (Delacroix) like the poet (Byron) or the revolutionary/warrior (Garibaldi) was considered to be a Romantic hero.

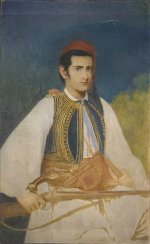

Byron and Garibaldi actually had other connections besides their military exploits. Both men liked adopting aspects of the exotic local clothing where they had carried out there heroic exploits. Byron, during his Grand Tour of the Mediterranean and Greece between 1809 and 1811 fell in love with the local costumes of Albania and brought one back with him. He even had his portrait done wearing it by the English painter Thomas Phillips in 1813. The costume is

still extant and has been occasionally displayed for the public in England. Some of Garibaldi's earliest exploits had taken place in Argentina during the 1830s where he admired the clothing of the gauchos. That influence may be seen in the illustration below.

Finally Byron as a revolutionary was a member of the secret society of the Italian Carbonari or charcoal burners which was inspired by the symbols and rituals of Freemasonry. It was one of a number of secret organizations that developed in the years leading up to the European Revolutions of 1848. These included Young Italy, Young Germany, Young Hungary, Young Poland, Etc. Giuseppe Mazzini, the Italian revolutionary ideologue of the Risorgimento and mentor to Garibaldi was also a Carbonari member.

Ilustrations:

1.Theodoros Vryzakis (1861) The Reception of Lord Byron at Missolonghi. 1825 Edition of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage

2.Eugene Delacroix (1824) The Massacre at Chios (1824) and Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi (1826

3.Lord Byron in Albanian Costume. Garibaldi and Gaucho apparel

4.Carbonari: Symbols. Secret Meeting. Arrest of Carbonari. Giuseppe Mazzini Italian Revolutionary and Carbonari member