PolarBear

Major

- Joined

- Feb 24, 2007

- Messages

- 6,706

Part 6A The Red Garibaldi Jacket: The Italian Job, The French Connection, & The Lady of Spain

“The latest fashion is absolutely necessary for a painting. It’s what matters most” --Edouard Manet

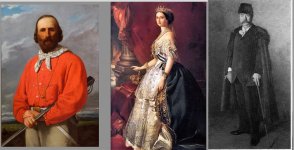

I will now consider the background to the red jacket worn by the woman on the bridge in Homer's The Old Mill. I will suggest sources both human and historical that were part of the jacket's creation in the 19th Century. In terms of individuals there are two: Giuseppe Garibaldi and Empress Eugenie of France.

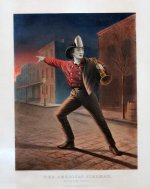

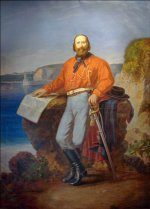

Garibaldi was the revolutionary, soldier and politician who was responsible for the unification of Italy in 1860 and Rome being made the capital in 1870. As I will show in a future post, Garibaldi was a major celebrity of the 19th Century and was known all over the world for his deeds and accomplishments during the era of European Nationalism in the years after the Revolutions of 1848. One of the things he was especially known for was the red shirt that he wore and the uniforms of his soldiers who were nicknamed the Carmicie rosse or redshirts. The redshirts that he and his men wore are believed to have made their first appearance during the 1840s while he was in exile in Latin America and fighting a war in Uruguay. Legend has it that the shirts came from a manufacturer in Montevideo that made red shirts that were worn by Argentinian butchers. Garibaldi and his men were able to get a supply of these. It was in Europe, however, during the Wars for Italian Independence that they became most famous and were recognized around the world. One of the interesting things I learned while researching Garibaldi was that he was actually born in what is now Nice France. At the time of his birth, however, it was still part of Italy.

The second influential individual credited with introducing the red Garibaldi Jacket was the wife of Emperor Napoleon III: Empress Eugenie de Montijo. Born in Spain she had married the Emperor in 1853. The Paris of Napoleon III was the city that had been designed and rebuilt by Baron Haussmann who added majestic boulevards and parks. These were new public spaces where people would gather and men and women could show off the latest styles of clothing. With the rise of the House of Worth, Paris became the fashion capital of the world. With improved railroad and steamship service visitors came to the City of Light from not only other European countries but also North America. This age also witnessed a rise in the importance of mass media. Empress Eugenie realized that in such an environment she could enhance her husband's administration through the world of fashion. She subsequently attached herself to the House of Worth with their rising reputation for creating and producing the latest styles in clothing for women. Eugenie ordered numerous outfits from Charles Worth and enhanced his already thriving business. This was also the age of the fashion magazine such as the American publication Godey's Lady's Book which reproduced the latest Parisian look, including illustrations (fashion plates)of the clothing worn by the Empress. She should be seen,therefore, as a forerunner to Princess Diana or the always stunning Duchess of Cambridge Kate Middleton in the promotion of the latest examples of fashion.

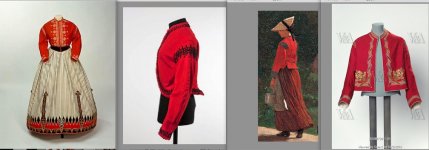

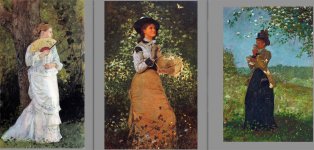

As a result of her involvement with fashion, Eugenie was responsible for introducing new styles and garments. Her popularity helped spread these styles around the globe. Among the styles she introduced was the Bolero Jacket based upon the jackets worn by Matadors in her native Spain. In the 1864 portrait of Mlle. L.L. by James Tissot, the young woman is wearing a red version decorated on the two front panels and the shoulders with ball fringe. The jacket was named for the bolero the Spanish dance done in imitation of the bullfight. Eugenie's high profile in Paris led to a fascination with Spain. Thus Manet did a number of paintings with Spanish themes including bullfighting. His 1862 Mlle. Victorine in the costume of a Matador is a good example. Manet's favorite model and mistress dressed in this manner parallels the popularity of the bolero jacket among women at the same time.

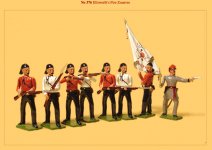

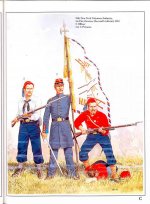

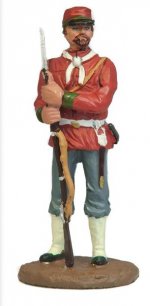

The bolero jacket shared similarities with the Zouave jacket a French military jacket influenced by styles from the Berbers of North Africa where France had established their military presence. The Zouave jacket differed from the Bolero in that the latter was not usually closed at the top. The other examples included in the illustrations below include a fashion plate from a an 1865 issue of Peterson's Magazine in red which shows the popularity of the Zouave jacket among women. The last image in that collage shows a red woman's jacket from 1865-66 that is described as a Zouave jacket but is open at the neck like a Bolero Jacket.

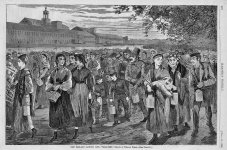

Finally, in this post, I have included a collage of illustrations related to the Zouave jacket's use by the military and by civilian women. The first image shows a French Zouave unit wearing the archetypal uniform in North Africa. The second is Winslow Homer's 1864 painting The Brierwood Pipe showing New York Zouaves in camp during the Civil War when regiments in both the North and South adopted this North African style for their uniforms. The last illustration in the group is an American made Day Dress in White Cotton with black Soutache decoration done in imitation of the North African decoration on both the jacket and skirt dating between 1862-1864 .

Part 6A

Illustrations:

1. Red Jacket detail from Homer’s Old Mill 1871

2. Giuseppe Garibaldi

Empress Eugenie

Charles F. Worth

3. Manet: Mlle. Victorine in the Costume of a Matador 1862

Tissot: Portrait of Mlle. L.L. 1864

Peterson’s Magazine 1865: Woman with Red Zouave Jacket

Zouave Jacket 1865-1866

4. French Zouaves North Africa

Homer: 1864 The Brierwood Pipe

Day Dress (American) 1862-1864

Next Time: Evolution of The Garibaldi: From Shirt to Jacket

“The latest fashion is absolutely necessary for a painting. It’s what matters most” --Edouard Manet

I will now consider the background to the red jacket worn by the woman on the bridge in Homer's The Old Mill. I will suggest sources both human and historical that were part of the jacket's creation in the 19th Century. In terms of individuals there are two: Giuseppe Garibaldi and Empress Eugenie of France.

Garibaldi was the revolutionary, soldier and politician who was responsible for the unification of Italy in 1860 and Rome being made the capital in 1870. As I will show in a future post, Garibaldi was a major celebrity of the 19th Century and was known all over the world for his deeds and accomplishments during the era of European Nationalism in the years after the Revolutions of 1848. One of the things he was especially known for was the red shirt that he wore and the uniforms of his soldiers who were nicknamed the Carmicie rosse or redshirts. The redshirts that he and his men wore are believed to have made their first appearance during the 1840s while he was in exile in Latin America and fighting a war in Uruguay. Legend has it that the shirts came from a manufacturer in Montevideo that made red shirts that were worn by Argentinian butchers. Garibaldi and his men were able to get a supply of these. It was in Europe, however, during the Wars for Italian Independence that they became most famous and were recognized around the world. One of the interesting things I learned while researching Garibaldi was that he was actually born in what is now Nice France. At the time of his birth, however, it was still part of Italy.

The second influential individual credited with introducing the red Garibaldi Jacket was the wife of Emperor Napoleon III: Empress Eugenie de Montijo. Born in Spain she had married the Emperor in 1853. The Paris of Napoleon III was the city that had been designed and rebuilt by Baron Haussmann who added majestic boulevards and parks. These were new public spaces where people would gather and men and women could show off the latest styles of clothing. With the rise of the House of Worth, Paris became the fashion capital of the world. With improved railroad and steamship service visitors came to the City of Light from not only other European countries but also North America. This age also witnessed a rise in the importance of mass media. Empress Eugenie realized that in such an environment she could enhance her husband's administration through the world of fashion. She subsequently attached herself to the House of Worth with their rising reputation for creating and producing the latest styles in clothing for women. Eugenie ordered numerous outfits from Charles Worth and enhanced his already thriving business. This was also the age of the fashion magazine such as the American publication Godey's Lady's Book which reproduced the latest Parisian look, including illustrations (fashion plates)of the clothing worn by the Empress. She should be seen,therefore, as a forerunner to Princess Diana or the always stunning Duchess of Cambridge Kate Middleton in the promotion of the latest examples of fashion.

As a result of her involvement with fashion, Eugenie was responsible for introducing new styles and garments. Her popularity helped spread these styles around the globe. Among the styles she introduced was the Bolero Jacket based upon the jackets worn by Matadors in her native Spain. In the 1864 portrait of Mlle. L.L. by James Tissot, the young woman is wearing a red version decorated on the two front panels and the shoulders with ball fringe. The jacket was named for the bolero the Spanish dance done in imitation of the bullfight. Eugenie's high profile in Paris led to a fascination with Spain. Thus Manet did a number of paintings with Spanish themes including bullfighting. His 1862 Mlle. Victorine in the costume of a Matador is a good example. Manet's favorite model and mistress dressed in this manner parallels the popularity of the bolero jacket among women at the same time.

The bolero jacket shared similarities with the Zouave jacket a French military jacket influenced by styles from the Berbers of North Africa where France had established their military presence. The Zouave jacket differed from the Bolero in that the latter was not usually closed at the top. The other examples included in the illustrations below include a fashion plate from a an 1865 issue of Peterson's Magazine in red which shows the popularity of the Zouave jacket among women. The last image in that collage shows a red woman's jacket from 1865-66 that is described as a Zouave jacket but is open at the neck like a Bolero Jacket.

Finally, in this post, I have included a collage of illustrations related to the Zouave jacket's use by the military and by civilian women. The first image shows a French Zouave unit wearing the archetypal uniform in North Africa. The second is Winslow Homer's 1864 painting The Brierwood Pipe showing New York Zouaves in camp during the Civil War when regiments in both the North and South adopted this North African style for their uniforms. The last illustration in the group is an American made Day Dress in White Cotton with black Soutache decoration done in imitation of the North African decoration on both the jacket and skirt dating between 1862-1864 .

Part 6A

Illustrations:

1. Red Jacket detail from Homer’s Old Mill 1871

2. Giuseppe Garibaldi

Empress Eugenie

Charles F. Worth

3. Manet: Mlle. Victorine in the Costume of a Matador 1862

Tissot: Portrait of Mlle. L.L. 1864

Peterson’s Magazine 1865: Woman with Red Zouave Jacket

Zouave Jacket 1865-1866

4. French Zouaves North Africa

Homer: 1864 The Brierwood Pipe

Day Dress (American) 1862-1864

Next Time: Evolution of The Garibaldi: From Shirt to Jacket