Great subject for a thread Shane.

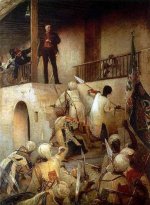

For those interested in history Queen Victorias reign has some great personalities, leaders, campaigns and interesting opponents (Russians, Afghans, Mutineers, Mahdists, Zulus and Boer Guerillas etc). Charges, sieges and relief expeditions etc. and some fascinating careers.

The Crimean War has always been a favourite mainly due to Charge of the Light Brigade, The Thin Red Line, famous artworks, the famous poem etc and the feud between the leaders Lord Lucan and the Earl of Cardigan who were brothers in law who barely spoke to each other.

This was the era of basically buying promotions/commands and as Wiki says about Cardigan :

"On 6 May 1824, at the age of 27, he joined the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars.Making extensive use of the purchase of commissions system then in use he became a Lieutenant in January 1825, a Captain in June 1826, a Major in August 1830 and a Lieutenant-Colonel, albeit on half-pay, only three months later, on 3 December 1830. He obtained command of the 15th The King's Hussars—at a reported premium of £35,000—on 16 March 1832."

and he went on to command the Light Brigade after a few scandals (one over a drink served in the Mess). Unfortunately he did not have much time for the experienced officers who had served in India.

The Reason Why by Cecil Woodham-Smith although published in 1953 is a good read explaining all the background.

Then there is the Indian Mutiny which is also an interesting period. The careers of some of the Generals of this period are great reads and I have spent quite a few hours jumping from name to name and battle etc on Wiki. Quite a few earned Victoria Crosses and they include :

Field Marshal Garnet Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley: Victoria Cross winner and commander of expeditionary forces in Africa, serving notably in the Indian Mutiny, Ashanti Wars, Anglo-Egyptian War, and serving as commander of the Gordon Relief Expedition in the Mahdist War.

Field Marshal Sir Evelyn Wood: Victoria Cross winner and commander of troops in the Zulu War and the Mahdist War.

Field Marshal Lord Roberts VC : Longtime British army officer in India and senior commander in the Second Afghan War; commander at one point in the Second Boer War. Check out all the campaigns he served in. Could have worn a great "been there done that" T shirt. Son awarded VC posthumously for Colenso and his father first to wear two VC's.

Check out the family of General Hugh Gough VC. His brother was a General with VC as was his Nephew and his Grandfather and Great Uncle were Field Marshalls.

However I do agree with Louis about MAGJEN Hector MacDonald who rose through the ranks. Very difficult to do at that time.

Also going on at this time was The Great Game, title of a good book by Peter Hopkirk summarised by Amazon below

"For nearly a century the two most powerful nations on earth, Victorian Britain and Tsarist Russia, fought a secret war in the lonely passes and deserts of Central Asia. Those engaged in this shadowy struggle called it "The Great Game," a phrase immortalized by Kipling. When play first began, the two rival empires lay nearly 2,000 miles apart. By the end, some Russian outposts were within 20 miles of India. This classic book tells the story of the Great Game through the exploits of the young officers, both British and Russian, who risked their lives playing it. Disguised as holy men or native horse-traders, they mapped secret passes, gathered intelligence, and sought the allegiance of powerful khans. Some never returned".

Very interesting times. About time somebody did a another movie of this period.

Brett