jazzeum

Four Star General

- Joined

- Apr 23, 2005

- Messages

- 38,888

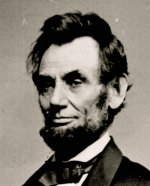

Grant Goes to War

A profile of General Ulysses from his birth in the region in Southern Ilinois known as Egypt (a reference to the supposed similarity between the Nile Delta and the fertile soil found at the confluence of the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee Rivers) until he occupied parts of Kentucky in September 1861.

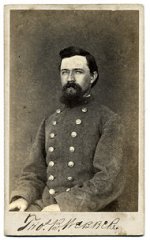

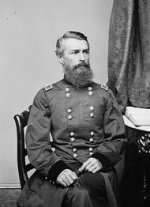

General Grant, 1861

Kentucky, at the outset of the Civil War, declared itself independent of both sides and would align with the side that was not the first to invade. However, Grant wanted to force the issue. In the end Grant took some daring moves that made the Confederates take the first step which led to the solidly Unionist legislature to overrule the Governor. The Governor complied, ending neutrality and declaring that Kentucky would side with the United States.

The full article can be accessed here.

A profile of General Ulysses from his birth in the region in Southern Ilinois known as Egypt (a reference to the supposed similarity between the Nile Delta and the fertile soil found at the confluence of the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee Rivers) until he occupied parts of Kentucky in September 1861.

General Grant, 1861

Kentucky, at the outset of the Civil War, declared itself independent of both sides and would align with the side that was not the first to invade. However, Grant wanted to force the issue. In the end Grant took some daring moves that made the Confederates take the first step which led to the solidly Unionist legislature to overrule the Governor. The Governor complied, ending neutrality and declaring that Kentucky would side with the United States.

The full article can be accessed here.

![Guidelines_Aug07-5[1].jpg Guidelines_Aug07-5[1].jpg](https://forum.treefrogtreasures.com/data/attachments/58/58530-c04f5e8741067c6e5ce9fcbd21377fc4.jpg)