jazzeum

Four Star General

- Joined

- Apr 23, 2005

- Messages

- 38,888

A War Not for Abolition

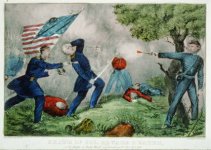

In September 1861, over 1,000 soldiers marched through Manhattan singing "reverentially and enthusiastically in praise of John Brown," as one observer of the scene put it. Thousands of private citizens joined in the celebration of John Brown's noble in "the cause of freedom." This scene caused consternation to those who favored the Civil War as a battle to preserve the Union and one not for abolition, as set forth by the New York Herald.

These two competing goals had been there from the very beginning. What the Union fought for has been the subject of much debate and Gary Gallagher has recently published a recent book on the matter.

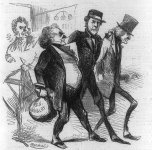

Those opposed to making the Civil War as a war against abolition claimed that the abolitionists had caused the Civil War with the hope of ending slavery and when secession did not lead to slavery, they then sought to convert the War into one of emancipation. This was generally true and abolitionist editors and speakers were from the very beginning trying to make this into a war about ending slavery, starting with William Lloyd Garrison, editor of the Liberator. Senator Charles Sumner had also been favoring emancipation as the principal goal of the Civil War.

William Lloyd Garrison

However, Lincoln would initially resist the goal of the Civil War as one for emancipation. Even when he embraced it as a military strategy, he did not feel he had the authority to pursue abolition in and of itself.

The full article can be accessed here.

In September 1861, over 1,000 soldiers marched through Manhattan singing "reverentially and enthusiastically in praise of John Brown," as one observer of the scene put it. Thousands of private citizens joined in the celebration of John Brown's noble in "the cause of freedom." This scene caused consternation to those who favored the Civil War as a battle to preserve the Union and one not for abolition, as set forth by the New York Herald.

These two competing goals had been there from the very beginning. What the Union fought for has been the subject of much debate and Gary Gallagher has recently published a recent book on the matter.

Those opposed to making the Civil War as a war against abolition claimed that the abolitionists had caused the Civil War with the hope of ending slavery and when secession did not lead to slavery, they then sought to convert the War into one of emancipation. This was generally true and abolitionist editors and speakers were from the very beginning trying to make this into a war about ending slavery, starting with William Lloyd Garrison, editor of the Liberator. Senator Charles Sumner had also been favoring emancipation as the principal goal of the Civil War.

William Lloyd Garrison

However, Lincoln would initially resist the goal of the Civil War as one for emancipation. Even when he embraced it as a military strategy, he did not feel he had the authority to pursue abolition in and of itself.

The full article can be accessed here.