jazzeum

Four Star General

- Joined

- Apr 23, 2005

- Messages

- 38,889

Caught Out of Time

A look at the Slave Narrative Project, a program dedicated to recording in print and recordings the voices of former slaves. The Slave Narrative Project was created by the Federal Writers Project of the Works Progress Administration during the New Deal Era. The Slave Narrative Project consisted of approximately 2,000 interviews from over 17 states. Only 27 interviews of this vast collection were tape recorded, and of those, only a handful specifically recall the Civil War. There are many other non-audio records of slaves’ memories of the conflict.

One former slave, Fountain Hughes, who was descended from Elizabeth Hemmings of Monticello, is heard to say, among other things, that he would rather shoot himself than go back to slavery where "you are nothing but a dog." He also decries the Yankees throwing flour into the river.

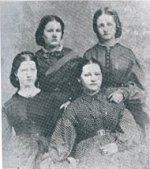

Julia Ann Jackson, age 102. Her photo was taken as part of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project slave narratives collections

Fountain Hughes, a former slave whose voice was recorded by the Slave Narrative Project

Although the Slave Narrative Project had a few drawbacks -- almost all the interviewers were white, many white Southeners were opposed to the project and some of the more damming recollections were censored -- there are glittering moments of candor in these narratives, and the effect of hearing rather than seeing or reading is a heightened contact with history.

As the author of the piece recounts, there is a priceless intimacy to tuning into the cadence and tone of someone recounting childhood memories punctuated by overseers and Yankees, surreptitious mistresses and cannon shots in the distance. Alice Gaston recalls the Federal army arriving on her plantation: “I can remember when the Yankees come through and they carried my father … Missus told me not say anything. They all hiding in the woods and I didn’t tell them anything.” Samuel Polite, speaking in Gullah dialect in St. Helena Island, SC, remembers his cruel overseer — “the devil” — making his mother plow, and Northern troops telling him to run away: “The Yankees come across on the old Giddy Main. They tell us to run away up in Bonrad.”

These narratives are as poetic as they are complex, tendentious and subtle; they spotlight the voices of those who had the most at stake in the war and lived to see it from the longest view.

The full article can be accessed here.

Note: the article contains several links to the tales of former slaves recorded by the Slave Narrative Project.

A look at the Slave Narrative Project, a program dedicated to recording in print and recordings the voices of former slaves. The Slave Narrative Project was created by the Federal Writers Project of the Works Progress Administration during the New Deal Era. The Slave Narrative Project consisted of approximately 2,000 interviews from over 17 states. Only 27 interviews of this vast collection were tape recorded, and of those, only a handful specifically recall the Civil War. There are many other non-audio records of slaves’ memories of the conflict.

One former slave, Fountain Hughes, who was descended from Elizabeth Hemmings of Monticello, is heard to say, among other things, that he would rather shoot himself than go back to slavery where "you are nothing but a dog." He also decries the Yankees throwing flour into the river.

Julia Ann Jackson, age 102. Her photo was taken as part of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project slave narratives collections

Fountain Hughes, a former slave whose voice was recorded by the Slave Narrative Project

Although the Slave Narrative Project had a few drawbacks -- almost all the interviewers were white, many white Southeners were opposed to the project and some of the more damming recollections were censored -- there are glittering moments of candor in these narratives, and the effect of hearing rather than seeing or reading is a heightened contact with history.

As the author of the piece recounts, there is a priceless intimacy to tuning into the cadence and tone of someone recounting childhood memories punctuated by overseers and Yankees, surreptitious mistresses and cannon shots in the distance. Alice Gaston recalls the Federal army arriving on her plantation: “I can remember when the Yankees come through and they carried my father … Missus told me not say anything. They all hiding in the woods and I didn’t tell them anything.” Samuel Polite, speaking in Gullah dialect in St. Helena Island, SC, remembers his cruel overseer — “the devil” — making his mother plow, and Northern troops telling him to run away: “The Yankees come across on the old Giddy Main. They tell us to run away up in Bonrad.”

These narratives are as poetic as they are complex, tendentious and subtle; they spotlight the voices of those who had the most at stake in the war and lived to see it from the longest view.

The full article can be accessed here.

Note: the article contains several links to the tales of former slaves recorded by the Slave Narrative Project.