jazzeum

Four Star General

- Joined

- Apr 23, 2005

- Messages

- 38,888

The Limits of Lincoln's Mercy

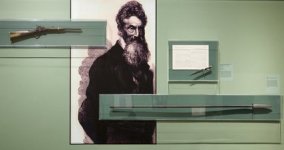

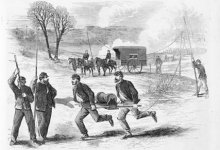

February 21, 1862. Nathaniel Gordon, a slave trader, becomes the only in American history to be executed for that crime.

The execution of Nathaniel Gordon

When Gordon was convicted, his lawyers only had one recourse open to him: an appeal to the President. During the Civil War, Lincoln was a man who would not countenance taking life if no good would be served. He gained the most notoriety in his actions in military cases. He was “unwilling for any boy under 18 to be shot,” and he had a tendency to pardon youths who had fallen asleep on guard duty or had deserted.

Some of his cabinet members felt that he had to be protected from his kinder instincts. His attorney general, Edward Bates said that he had but one failing, "I have sometimes told him he was unfit to be entrusted with the pardoning power. Why, if a man comes to him with a touching story his judgment is almost certain to be affected by it. Should the applicant be a woman — a wife, a mother or a sister — in 9 cases out of 10 her tears, if nothing else, are sure to prevail.”

However, he did believe that there are some cases where the law must be carried out and the Gordon case was such a case.

When Captain Gordon's family, along with the wife of a strong supporter of Lincoln's, visited the White House to plead for clemency, Lincoln refused to see them.

Why? Although he hated slavery, he did not feel he had the legal right to interfere with the question of slavery as it presently existed. However, he abhorred slave trading and in any event it was against the law. Said Lincoln:

The full article can be accessed here.

February 21, 1862. Nathaniel Gordon, a slave trader, becomes the only in American history to be executed for that crime.

The execution of Nathaniel Gordon

When Gordon was convicted, his lawyers only had one recourse open to him: an appeal to the President. During the Civil War, Lincoln was a man who would not countenance taking life if no good would be served. He gained the most notoriety in his actions in military cases. He was “unwilling for any boy under 18 to be shot,” and he had a tendency to pardon youths who had fallen asleep on guard duty or had deserted.

Some of his cabinet members felt that he had to be protected from his kinder instincts. His attorney general, Edward Bates said that he had but one failing, "I have sometimes told him he was unfit to be entrusted with the pardoning power. Why, if a man comes to him with a touching story his judgment is almost certain to be affected by it. Should the applicant be a woman — a wife, a mother or a sister — in 9 cases out of 10 her tears, if nothing else, are sure to prevail.”

However, he did believe that there are some cases where the law must be carried out and the Gordon case was such a case.

When Captain Gordon's family, along with the wife of a strong supporter of Lincoln's, visited the White House to plead for clemency, Lincoln refused to see them.

Why? Although he hated slavery, he did not feel he had the legal right to interfere with the question of slavery as it presently existed. However, he abhorred slave trading and in any event it was against the law. Said Lincoln:

I believe I am kindly enough in nature, and can be moved to pity and to pardon the perpetrator of almost the worst crime that the mind of man can conceive or the arm of man can execute; but any man, who, for paltry gain and stimulated only by avarice, can rob Africa of her children to sell into interminable bondage, I never will pardon.

The full article can be accessed here.