You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

"The Zulu War" (2 Viewers)

- Thread starter The Lt.

- Start date

The Lt.

Memoriam Member

- Joined

- Dec 10, 2006

- Messages

- 9,076

Enjoyed your photos Martyn the second time around as much as I did the first time

Ran across two more photos that may have come from the Illustrated London News Martyn one features a Zulu Warrior claiming his second victory joined shortly by his Induna.....Joe.

Ran across two more photos that may have come from the Illustrated London News Martyn one features a Zulu Warrior claiming his second victory joined shortly by his Induna.....Joe.

GICOP

Four Star General

- Joined

- Oct 16, 2008

- Messages

- 28,319

Enjoyed your photos Martyn the second time around as much as I did the first time

Ran across two more photos that may have come from the Illustrated London News Martyn one features a Zulu Warrior claiming his second victory joined shortly by his Induna.....Joe.

Great pictures Joe, could well be ILN {bravo}}{bravo}}{bravo}}

Just picked up the bound volume ILN July to December 1898 with a great fold out of the Charge of the 21st Lancers :wink2:

Cheers mate

Martyn

mikemiller1955

Lieutenant General

- Joined

- Aug 3, 2008

- Messages

- 17,797

Great black and whites Joe...they look spectacular!!!

The Lt.

Memoriam Member

- Joined

- Dec 10, 2006

- Messages

- 9,076

Got to enjoy your photos shared with us from the Illustrated London News Martyn and thanks Michael and Jeff for your comments an Looking forward Jeff to seeing your new arrivals.

Ran across a few more photos I thought I'd share with you.

Ran across a few more photos I thought I'd share with you.

GICOP

Four Star General

- Joined

- Oct 16, 2008

- Messages

- 28,319

Got to enjoy your photos shared with us from the Illustrated London News Martyn and thanks Michael and Jeff for your comments an Looking forward Jeff to seeing your new arrivals.

Ran across a few more photos I thought I'd share with you.

Great pictures Joe, I knew I had seen a similar one before

Cheers mate

Martyn

GICOP

Four Star General

- Joined

- Oct 16, 2008

- Messages

- 28,319

Seeing I've used your photos in creating a number of my Calendars featured on the forum it was nice of you to feature one of mine featuring it in your creative Illustrated London News. Thank you good sir.

Your picture was made for the cover of an ILN Joe {bravo}}{bravo}}{bravo}}

Cheers mate

Martyn

The Lt.

Memoriam Member

- Joined

- Dec 10, 2006

- Messages

- 9,076

Ian Knight on the Battle of Isandlwana......The Lt.

http://www.1879zuluwar.com/t5846-battle-of-isandlwana-ian-knight#36797

http://www.1879zuluwar.com/t5846-battle-of-isandlwana-ian-knight#36797

mikemiller1955

Lieutenant General

- Joined

- Aug 3, 2008

- Messages

- 17,797

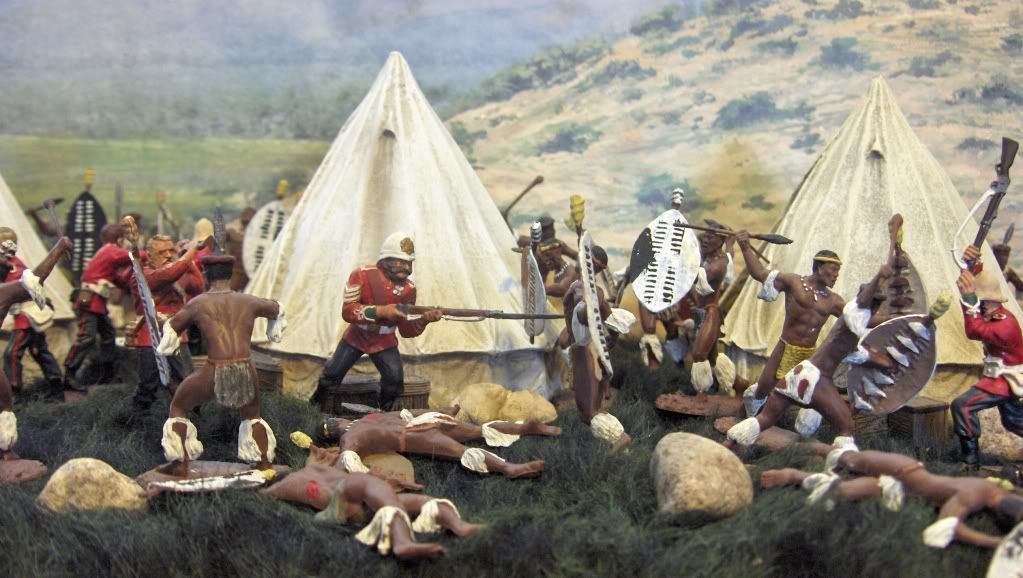

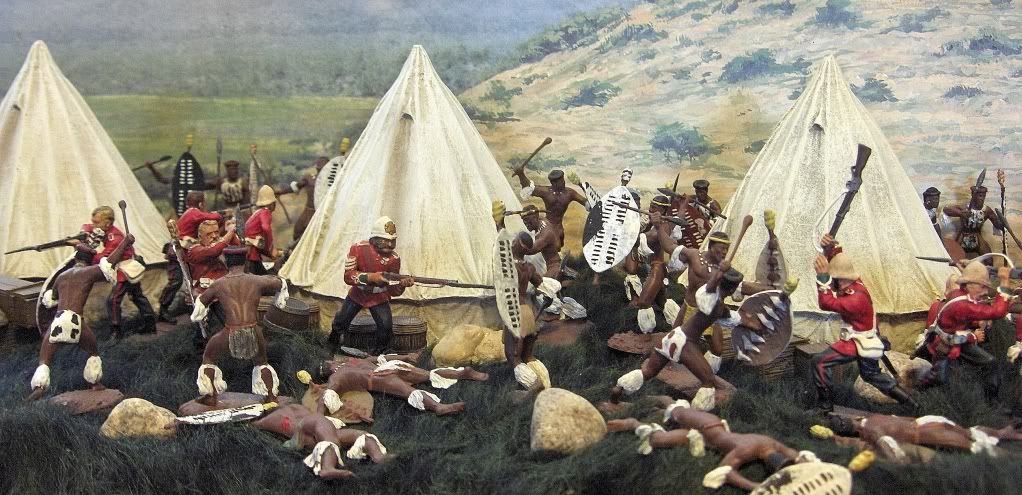

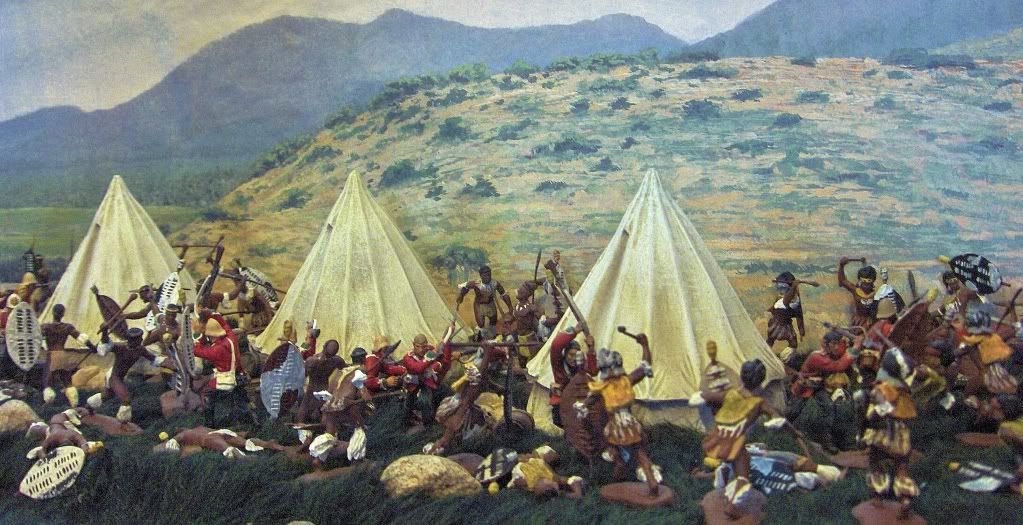

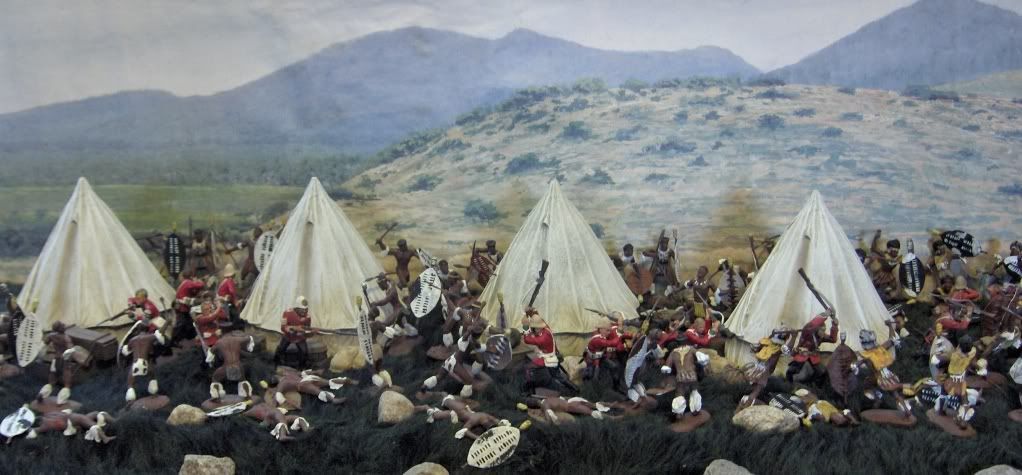

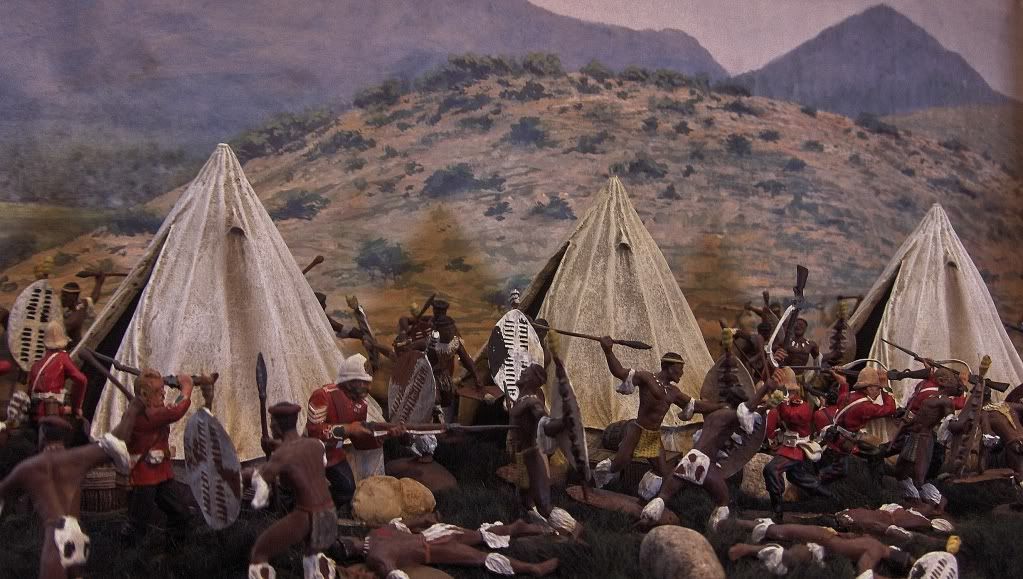

Joe...that's a great picture...probably pretty close to what it really looked like...

The Lt.

Memoriam Member

- Joined

- Dec 10, 2006

- Messages

- 9,076

Thanks Michael my original photo was enhnce by a friend to create the overall efffect to create the photo.

WAS MELVILL ORDER TO SAVE THE COLORS

This from the kwazulu Website.

"It is one of the most stirring moments in the dramatic story of the battle. As the Zulus burst through the British line, and all is about to be lost, Col. Pulleine, in command of the camp, called Lts. Melvill and Coghill of the 1/24th to him, and gave the Queen's Colour of the battalion - the symbol of regimental and national pride - into their care, ordering them to 'take it to a place of safety'. Together, Melvill and Coghill dash across country, braving the horrors of the Zulu pursuit, only to lose the Colour in the raging Mzinyathi (Buffalo) River, on the very threshold of safety. Having crossed the river, both men are tragically overtaken and killed.

This view is very much a construct of the times, created to soothe the 24th's wounded pride, and to provide the British public with an unequivocal image of selfless heroism with which to offset the horror of the defeat.

Needless to say, it didn't happen quite like that, either. None of the British survivors of the battle claimed to have seen Pulleine hand the Colour to Melvill, and in fact the story first appeared a month or so after the battle, attributed to an anonymous source. Almost certainly, the story originated among surviving officers of the 24th, keen to ensure that Melvill's actions appeared in a suitably heroic light. In fact, as Adjutant of the 1/24th, the care of the Colours fell in any case within Melvill's responsibilities.It is far more likely that he fetched the Colour in an attempt to rally the battalion - but then found that it was too late, and instead tried to carry them away. He did not leave the camp with Coghill - several witnesses saw them riding away separately - and in fact the two don't seem to have joined up until they reached the river. Melvill, of course, lost the Colour in the flooded river and was nearly swept away himself, but Coghill - who had already reached the other side safely - returned to the water and saved him.

At the time, senior officers expressed reservations about the wisdom of recognising as heroic the actions of men who - however good the reason - were in fact abandoning the field. As Chelmsford himself put it, by saving the Colours Melvill 'was given the best chance of saving his life which must have been lost had he remained in camp … The question, therefore, remains had he succeeded in saving the colours and his own life, would he have been considered to have deserved the Victoria Cross?' In fact, however, the 'dash with the Colours', as the Press hailed it, had already caught the public imagination. There was no provision for the posthumous VC in 1879, but it was noted that Melvill and Coghill would have received it, had they lived. At the turn of the century, when posthumous awards were introduced, the award was confirmed, and VCs sent to their families."

WAS MELVILL ORDER TO SAVE THE COLORS

This from the kwazulu Website.

"It is one of the most stirring moments in the dramatic story of the battle. As the Zulus burst through the British line, and all is about to be lost, Col. Pulleine, in command of the camp, called Lts. Melvill and Coghill of the 1/24th to him, and gave the Queen's Colour of the battalion - the symbol of regimental and national pride - into their care, ordering them to 'take it to a place of safety'. Together, Melvill and Coghill dash across country, braving the horrors of the Zulu pursuit, only to lose the Colour in the raging Mzinyathi (Buffalo) River, on the very threshold of safety. Having crossed the river, both men are tragically overtaken and killed.

This view is very much a construct of the times, created to soothe the 24th's wounded pride, and to provide the British public with an unequivocal image of selfless heroism with which to offset the horror of the defeat.

Needless to say, it didn't happen quite like that, either. None of the British survivors of the battle claimed to have seen Pulleine hand the Colour to Melvill, and in fact the story first appeared a month or so after the battle, attributed to an anonymous source. Almost certainly, the story originated among surviving officers of the 24th, keen to ensure that Melvill's actions appeared in a suitably heroic light. In fact, as Adjutant of the 1/24th, the care of the Colours fell in any case within Melvill's responsibilities.It is far more likely that he fetched the Colour in an attempt to rally the battalion - but then found that it was too late, and instead tried to carry them away. He did not leave the camp with Coghill - several witnesses saw them riding away separately - and in fact the two don't seem to have joined up until they reached the river. Melvill, of course, lost the Colour in the flooded river and was nearly swept away himself, but Coghill - who had already reached the other side safely - returned to the water and saved him.

At the time, senior officers expressed reservations about the wisdom of recognising as heroic the actions of men who - however good the reason - were in fact abandoning the field. As Chelmsford himself put it, by saving the Colours Melvill 'was given the best chance of saving his life which must have been lost had he remained in camp … The question, therefore, remains had he succeeded in saving the colours and his own life, would he have been considered to have deserved the Victoria Cross?' In fact, however, the 'dash with the Colours', as the Press hailed it, had already caught the public imagination. There was no provision for the posthumous VC in 1879, but it was noted that Melvill and Coghill would have received it, had they lived. At the turn of the century, when posthumous awards were introduced, the award was confirmed, and VCs sent to their families."

villagehorse

Lieutenant General

- Joined

- Feb 5, 2010

- Messages

- 16,884

Yes Joe the black is out numbering the red easily suggesting black will prevail this time. Perfect representation of the final moments in the camp. Cheers, Robin.

mikemiller1955

Lieutenant General

- Joined

- Aug 3, 2008

- Messages

- 17,797

these are nice Joe...you know I'm a sucker for these epic battle scenes...well done...

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 3 (members: 0, guests: 3)